Nearly four decades after his wife's death, Ernest Stuart said her disappearance and the investigation into her murder are still “raw.”

Kristine Stuart was a unique person, her husband said, a beloved Lansing science teacher, a well-known community member.

And then she was gone.

Thirty-year-old Kristine Stuart went missing while walking on Fairoaks Court near Coolidge Road in East Lansing on Aug. 14, 1978.

She was the fourth known victim of serial killer Don Gene Miller who — more than 37 years after her murder — is up for parole.

“He was one of the coldest people I’ve ever seen or met. He had no expressions, no feeling,” Ernest Stuart said, after learning of the parole hearing from a Lansing State Journal reporter. “I can’t conceive of a situation where he would have any kind of consideration for any type of early release.”

Kristine Stuart disappeared just two days before Miller was arrested. He was captured hours after raping and attempting to kill a 14-year-old Delta Township girl.

He later would confess to the killings of Stuart and three other East Lansing women.

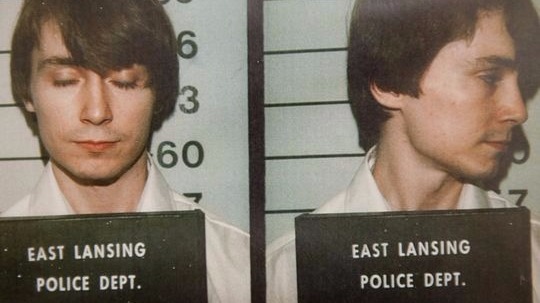

But the boyish-faced, Bible-carrying Miller was so good at covering his tracks that he was never convicted of murder.

The 61-year old Miller, who then-Eaton County Assistant Prosecutor G. Michael Hocking called “Michigan’s version of Ted Bundy,” will meet with a member of the state parole board next month.

Miller's first chance at parole since 1997 has reopened old wounds and fueled fresh fears.

An early chance at parole

“I don’t think Donald Miller should ever walk the streets of any city, period,” said retired Ingham County Circuit Judge Peter Houk, who served as Ingham County prosecutor from 1977 to 1986.

“He will kill again if he’s out.”

Like Houk, past and present prosecutors in Ingham and Eaton counties say they're committed to keeping Miller in prison and will meet with the parole board and victims' families to do so. East Lansing police also will address the parole board.

"The victims and the community should have a concern about Don Miller," Eaton County Prosecutor Doug Lloyd said. "It's my goal to make sure the parole board knows about the atrocities he committed.”

But lawyer Tom Bengtson said he believes his former client deserves a chance at freedom.

“He’s served his time,” Bengtson said. “I do think he’s no longer a threat to society … He’s spent the last 15 years in a prison cell with no assaultive behavior. I think that’s a pretty good test.”

In past parole hearings, prison officials described Miller as a quiet, polite inmate who worked at the prison newspaper, according to records from seven parole hearings held between 1989 and 1997.

The records, obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request, also refer to a “very sick man” who will be a “serious threat when released.”

“Mr. Miller presents himself as a very remorseful person — but not sure if he is genuine,” were among the notes from a 1993 parole hearing made by a parole board member. “Still expressed pain from rejection of his fiancée…Volcano ready to explode.”

Miller’s earliest release date was supposed to be in October 2018, but a Court of Appeals decision last year has pushed up his timeline for parole, Michigan Department of Corrections Spokesman Chris Gautz said.

If parole board members agree to grant Miller parole in the coming months, he next must get approvals from Eaton County Circuit Judge John Maurer and Chippewa County Circuit Judge James Lambros.

Miller, who is being held at the G. Robert Cotton Correctional Facility in Jackson, declined to be interviewed for this story.

If Miller serves his full sentence, he would be released at the age of 76 on March 24, 2031, according to MDOC records.

Donna Irish, the former stepmother of Lisa Gilbert, the 14-year-old girl Miller raped, said her concern over Miller’s chances at parole has increased with the passage of time — as champions for Miller’s continued imprisonment have died or moved to other positions.

“Is the outcome for us going to be as good as it was in the past?” Irish said. “Here I am, 82 and still alive and still feel just as strongly that I don’t want Miller out on the streets.”

East Lansing’s disappearing women

Don Miller killed his first known victim in the early hours of New Year's Day in 1977, as Houk began his first term as Ingham County prosecutor.

Martha Sue Young was a 19-year-old French major at Michigan State University. She had broken off her engagement with Miller three days before she went missing on Jan. 1, 1977.

Miller, who’d spent New Year’s Eve with Young, said he’d left her on the doorstep of her home about 2 a.m. Police didn’t believe his story.

“There was no body and no evidence, just a good suspicion,” Houk said. “(Miller) was the last person to see her alive, and his story didn’t hang together.”

On Oct. 20, 1977, two hunters found Young’s clothing and purse in thick underbrush near Potter Lake in Bath Township. The clothing was laid out with the undergarments inside of the outer clothing, “like she had ascended to heaven,” Houk said.

“This is a guy who’s playing with people,” he added.

Miller claimed his next known victim the following summer.

Marita Choquette, a 27-year-old editorial assistant at WKAR-TV, went missing on June 15, 1978.

About two weeks later, on June 27, 1978, Choquette’s mutilated body was found by a farmer about a half-mile behind his home on Okemos Road in Alaiedon Township.

Covered by several white cement blocks, Choquette's body lay on the ground with her feet tucked beneath her as if she had fallen back from a kneeling position. She had been stabbed 17 times. Her hands, severed from her arms, lay beside her.

That same day, 21-year-old Wendy Bush went missing.

Witnesses said they saw the blonde-haired, green-eyed junior at MSU walking with a tall white man on campus just before her disappearance.

More than a month later, 30-year-old Kristine Stuart went missing while walking home from an auto repair shop on Aug. 14, 1978. The science teacher’s tortoise shell glasses were left at the side of the road.

As police struggled to solve the disappearances, their main suspect was about to make a major misstep.

The rape that outed Don Miller

Two days after Stuart’s disappearance in East Lansing, 14-year-old Lisa Gilbert encountered Miller in her Canal Road home.

Miller asked the girl for a pencil and paper to write down a phone number, then forced her into a bedroom.

He raped Gilbert and began to strangle her when Randy Gilbert, Lisa’s 13-year-old brother, entered the home. Miller left Lisa to confront Randy.

Lisa ran outside, naked save the nylon stockings binding her wrists and one of her father’s ties around her neck. The tie had been used to gag her mouth.

Miller choked Randy Gilbert until he passed out, then stabbed him three times, twice in the chest and once in the neck.

An Oldsmobile worker, a fire chief, and a mother and daughter were driving by as Lisa ran onto Canal Road. All four stopped to help.

Miller fled in his 1973 brown Oldsmobile Cutlass.

James Regan, the Oldsmobile worker, and then-Delta Township Fire Chief Ken Dorin took down Miller’s license plate number and called police.

Regan described Miller to a reporter as “a nice looking guy. The kind you’d be proud to have your daughter go out with.”

Cheryl Krapf-Haddock was just 13 and was riding with her mother when they stopped to help. They took Lisa into their car and gave her clothing.

“There were so many police there so quickly,” Krapf-Haddock said. “I’ve never seen anything like it and will never forget it.”

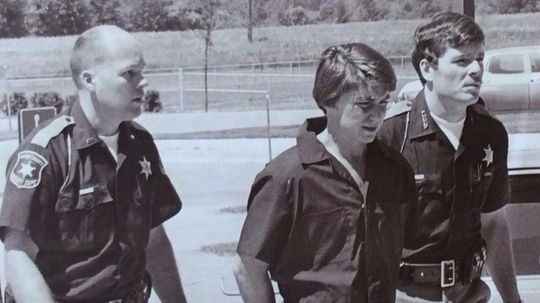

Miller was arrested later that day.

Both Lisa and Randy Gilbert survived.

A deal for bodies, closure

Miller was charged in Eaton County with rape and attempted murder for the attack on the Gilbert children. He was convicted on those charges in May of 1979 and sentenced to 30 to 50 years in prison.

Three months earlier, in February 1979, an Ingham County grand jury had indicted Miller on second-degree murder charges in the deaths of Young, his former fiancée, and Stuart, the East Lansing teacher.

The case never went to trial.

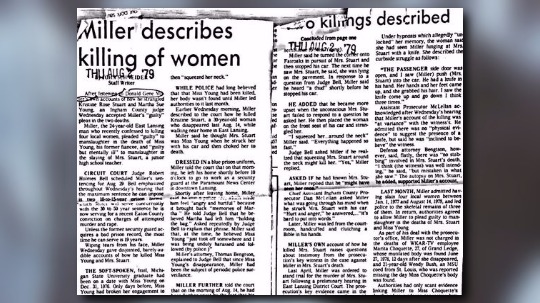

Instead, on July 13, Miller agreed to plead guilty to two counts of manslaughter in Ingham County in exchange for leading police to Young and Stuart’s bodies.

Young was found in Prigooris Park off Drumheller Road in Bath Township. Stuart was found in a drainage ditch in a farm field near Jason Road and Old U.S. 27 in Olive Township in Clinton County.

Three days later, Miller agreed to undergo a “memory jogging” session with a therapist during which he revealed details of Choquette's and Bush’s deaths. Miller led police to Bush's body in a small woodlot off St. Joseph Highway and Broadbent Road in Delta Township. He agreed to the regressive psychotherapy on the condition that he wouldn’t be charged in the two women’s deaths.

Miller told officials he choked Bush — who he’d once gone canoeing with — in a parking lot between Spartan Stadium and what was then the men’s intramural building.

Miller said he killed Choquette — who he’d known when she worked at the MSU library — after taking her out to breakfast. He told police he cut off her hands when he was unable to unlock the handcuffs he had placed on her wrists.

At Miller’s plea hearing in the Young and Stuart cases, he told Ingham County Circuit Judge Robert Holmes Bell that he’d strangled Young after she told him she didn’t love him.

He told Bell he hit Stuart with his car nearly two years later because he thought she was Young. When an unconscious Stuart did not answer questions after the crash, Miller strangled her.

Bell sentenced Miller to 10 to 15 years in prison. Since the sentence was concurrent, it didn’t add to Miller’s 30 to 50-year sentence in Eaton County.

Bell, now a U.S. District Court judge, remembers Miller as a “nice-looking, clean-spoken” man who seemed relaxed as he described the two murders.

Both Bell and Houk took heat for Miller’s plea deal and relatively light sentence.

“I didn’t have any choice,” Bell said. “At the time I took the plea and at the time I gave the sentence, I made it very clear that I was pretty much hamstrung.”

Houk said he discussed the plea agreement with family members prior to making the deal.

"I think people were justifiably upset with it, because those crimes were terrible crimes and he should have served life for them," Houk said. "But we had no way to get there. Understand, at that time, there were no bodies... I don’t think there was anyone more upset about it than prosecutors and police.”

Ernest Stuart said he believed a conviction on second-degree murder charges was a longshot given that prosecutors would rely largely on testimony from a hypnotized witness.

“It was an iffy thing and (Houk) told me that when they first started it, that they were taking a risk,” said Ernest Stuart, who has since remarried and moved from Michigan.

“That influenced my decision at the time.”

Kay Young, Martha Sue Young's sister, said her family understood that even a second-degree murder conviction likely would not have resulted in additional time for Miller since state law at the time required a concurrent sentence.

While a plea that included the disclosure of Martha Sue's body would not add years to Miller's sentence, it would provide some closure to the family.

"It was a very hard decision," Kay Young said in an email.

An ongoing fight

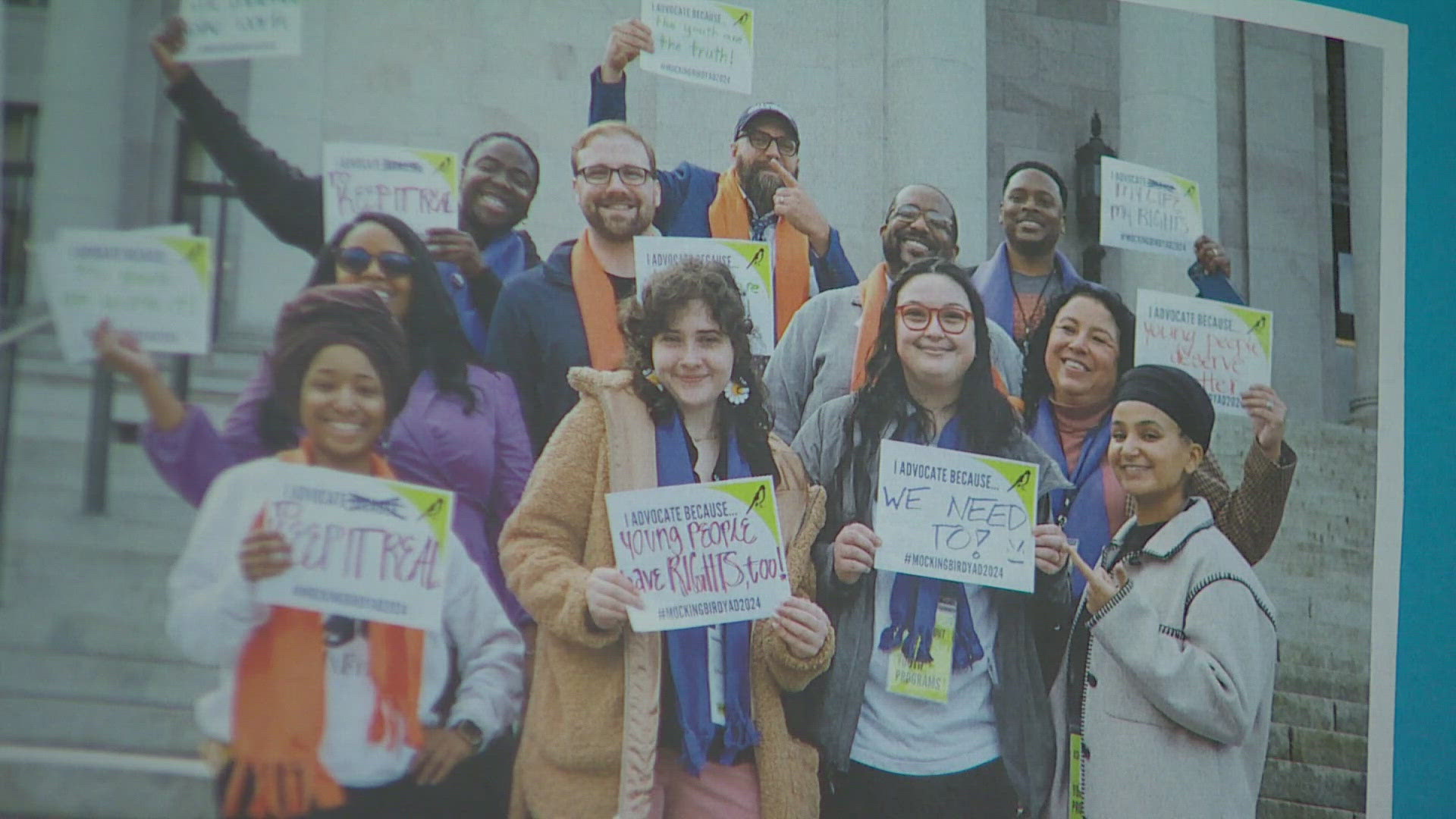

In 1997, concerned family members, residents and officials — including Ingham County Prosecutor Stuart Dunnings III and Eaton County Prosecutor Jeff Sauter — formed a group to keep Miller behind bars. The group was called the Committee for Community Awareness & Protection.

Sauter, who was appointed Circuit Court judge in Eaton County in 2013, died earlier this year. Dunnings resigned earlier this month and is facing criminal charges related to prostitution.

Dr. Frank Ochberg, a clinical professor of psychiatry at MSU and former associate director of the National Institute of Mental Health, led the committee.

“(Miller's) a very harmless-looking guy, and he’s the kind of guy who would be a model prisoner,” Ochberg said. “That’s one of the dangers, when this guy comes up (for parole) decades later, people looking at him don’t have the full history.”

While the committee studied ways to keep Miller behind bars, the group stumbled on a 1994 prison infraction in Miller’s MDOC record.

Prison officials had found a garrote — a strangling device made from a shoestring and barrel buttons — in Miller’s cell at Kinross Correctional Facility in Chippewa County.

“We believed that he was going to use them on a female corrections officer up there,” said Bob Dutcher, a former Meridian Township police captain who helped build the case against Miller.

Sauter and Dunnings, appointed as special prosecutors, took Miller to trial in Chippewa County, where a jury convicted him of possessing a weapon in prison.

Miller’s weapons charge tagged another 20 to 40 years to his sentence.

Bengtson, Miller’s original defense attorney who was retained again by Miller’s family for the case, called the charge and sentence “ridiculous.”

“I didn’t think it was factually grounded,” Bengtson said. “I expected him to walk out a free man.”

Worries about the future

Nearly four decades after her rape, Lisa Gilbert said she forgives Miller, but believes he is beyond rehabilitation. She plans to tell the parole board the same.

“My opinion counts,” said Gilbert, who has since married and moved out of Michigan. “I feel in a way that I’m not only speaking for my brother and I, but I’m speaking out for the other women who were robbed of their lives.”

Krapf-Haddock said she has never spoken publicly of her experience since testifying at Miller’s trial decades ago.

But a letter from the parole board in June, informing her of Miller’s latest chance at freedom, made her come forward, she said.

“It’s time for anybody who had anything to do with this case to make sure he doesn’t do this to our daughters, wives, mothers,” Krapf-Haddock said.

“The case is being forgotten. People are forgetting how dangerous this man is.”

Kay Young agrees.

“Because he is in a heavily controlled environment where he cannot kill others should not mislead people to the conclusion that he will choose not to kill again in free society,” Young said in an email. “Where he is now, others control his desire or fantasy to kill.”

Ochberg believes Miller is a sadistic psychopath, a lethal predator who will kill again if he’s released.

That’s why he and the committee campaigned nearly two decades ago to develop a form of civil commitment for killers who can’t be rehabilitated. The legislation to create such a system was unsuccessful.

“What do you do when someone’s served the sentence they were given," Ochberg said, "and they’re still deadly dangerous?”