A wave of earthquake tremors over the last few months have moved parts of Washington state and Vancouver Island westward.

They’ve been called “silent earthquakes," slow slip or deep tremors and can take months to play out; one just wrapped up that began in April. They occur when the oceanic and continental tectonic plates quietly slip past each other deep in the Earth.

These silent quakes weren't known to researchers 20 years ago. They were discovered in Japan, which has a similar geological structure to the northwest coast of the U.S. and southwestern Canada. That same structure expected to result in a magnitude nine earthquake and tsunami off the coast, much like what killed some 16,000 people in Japan in 2011.

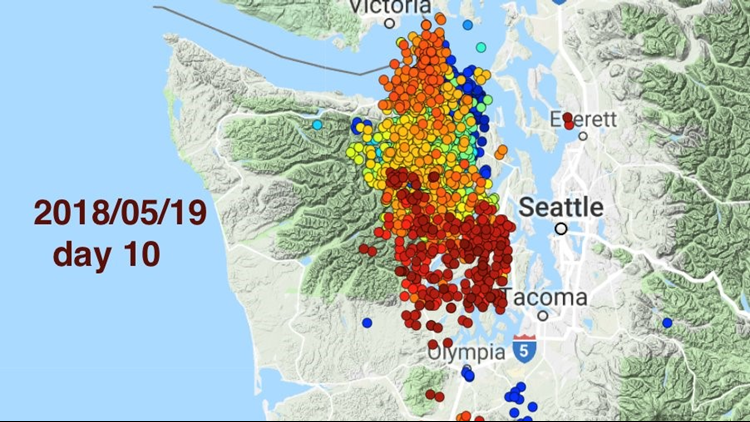

The recent tremor event began May 8 slightly north of previous tremors, according to the Pacific Northwest Seismic Network.

These tremors are plotted out as swarms move up and down the coast with no shaking felt. Yet they are large earthquakes, releasing enough energy to equal a magnitude 6.8.

The "lock zone," where the plates are stuck together, have the potential to form enough pressure to break and create big coastal earthquakes and tsunamis estimated at magnitude 9.

Discussions have renewed to learn how big the lock zone is, and how much closer is it to the major population centers of Seattle, Tacoma, Everett, Portland, Vancouver, B.C. The shaking for these locations could be even worse further east and closer to population centers than first thought. If proven, the theory could lead to changes in building codes and emergency preparation.

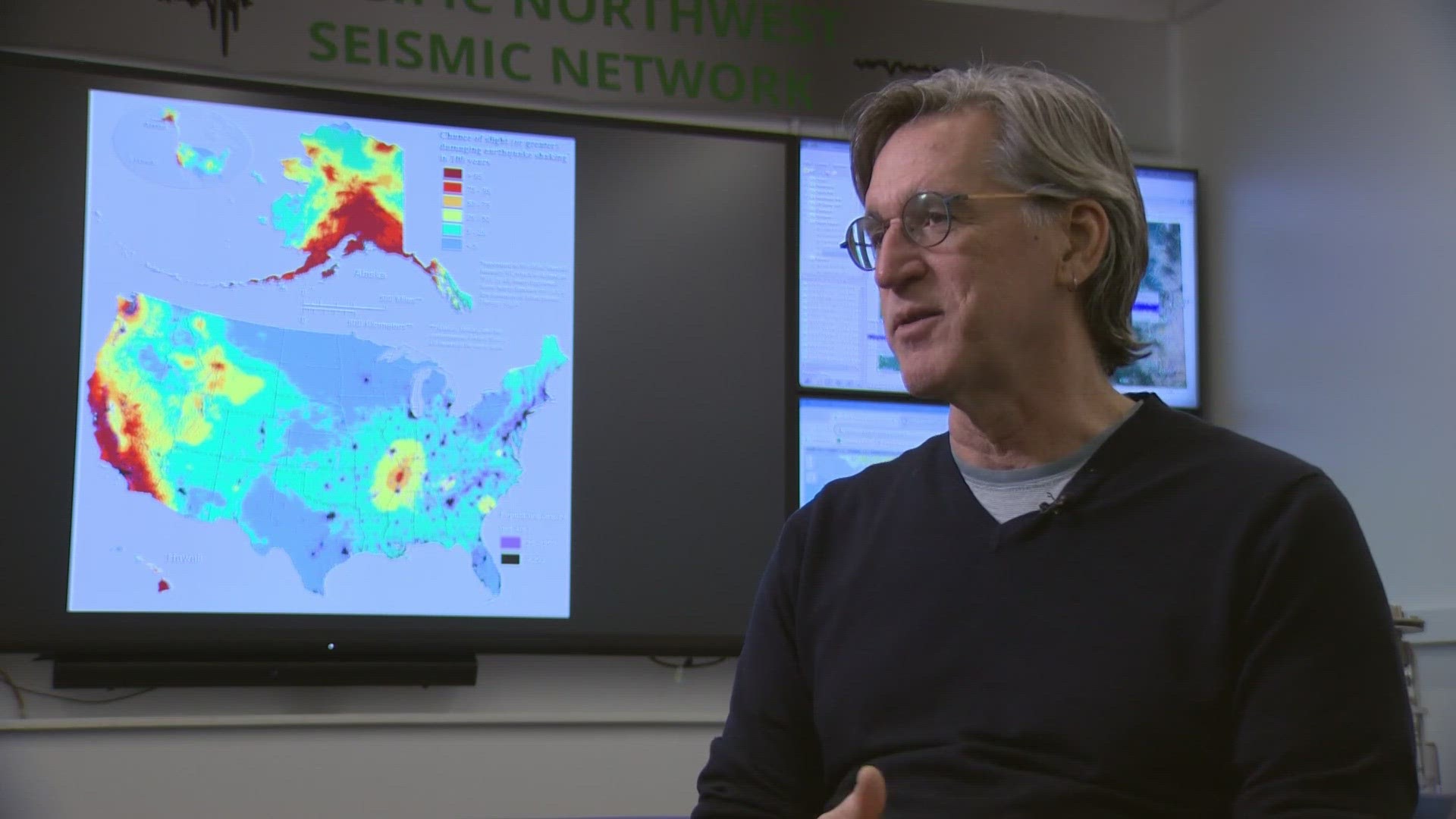

“This is something we have discussed in the past but is worth revisiting and rethinking,” said University of Washington Seismologist Ken Creager speaking of the theory that the western edge of the tremor could mark the eastern side of the lock zone.

“We have a number of ways of estimating where it is, but they don’t all give the same answer,” said Creager. “This is one of several possibilities, and I wouldn’t necessarily say it’s the most likely one.”

The last time the Cascadia Subduction Zone went off and caused a major earthquake was in 1700. It created a tsunami so big it was recorded in Japan.