WASHINGTON — The upper end of Discovery Bay in Jefferson County acts as a geological history book for tsunami waves.

In between thick layers of mud are layers of sand, which was brought in from near the Straight of Juan de Fuca by the power of inrushing tsunami waves. Some sand layers are thicker and wider than others.

In 2019, KING 5 watched as Carrie Garrison-Laney, the coastal hazards specialist for Sea Grant Washington, dug through that mud looking for a thin layer of sand driven in by the 1964 Alaska tsunami.

“We suspect that we know what our tsunami risks are,” said Garrison-Laney. “But I suspect the more work we do, the better we will have a handle on that.”

She also showed thick sand layers suspected of being generated by large tsunami generating earthquakes off the northwest coast hundreds of years in the past.

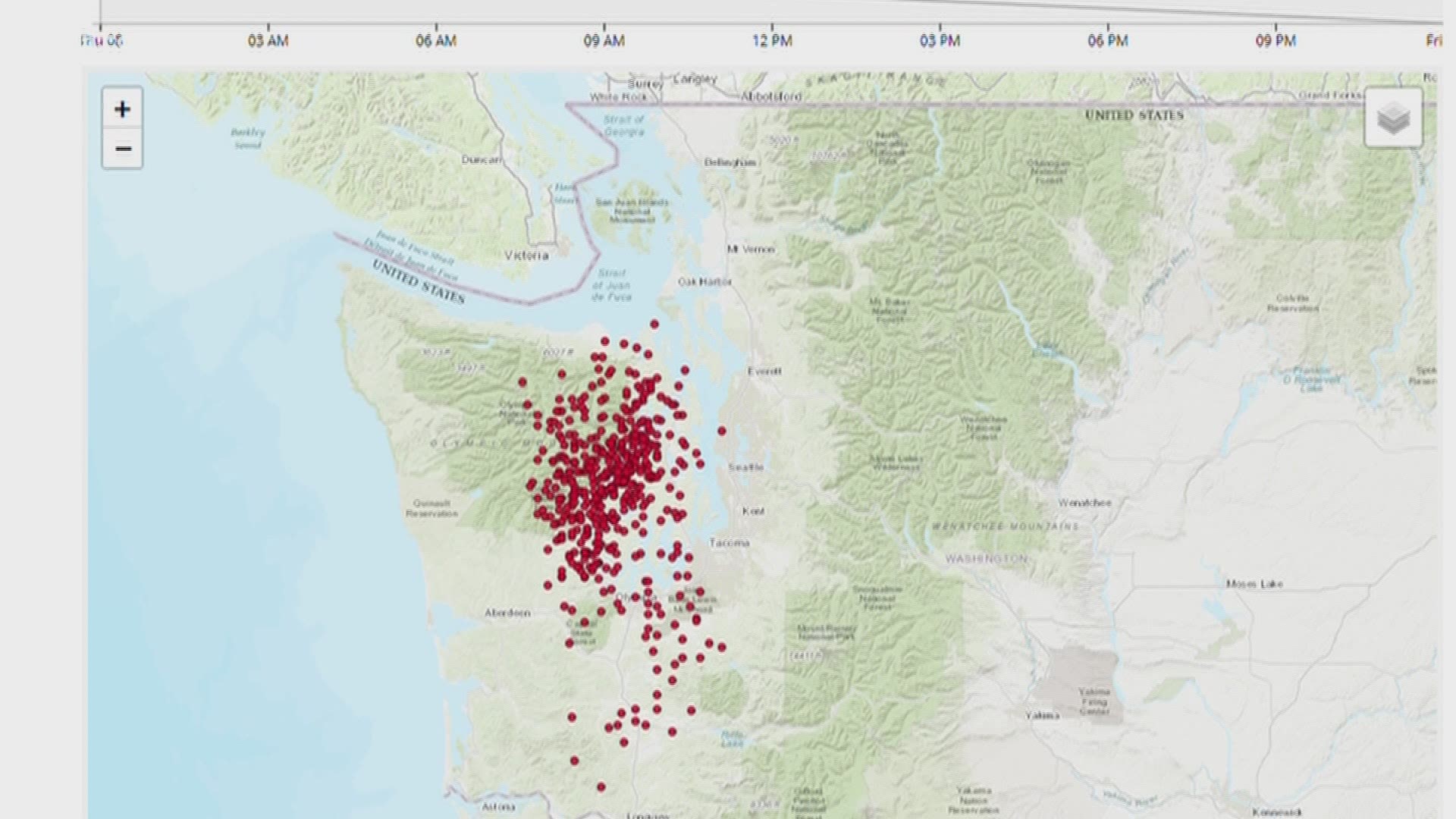

Monday’s magnitude 7.5 earthquake that struck offshore between the Alaska Peninsula and the Aleutian Trench was the second strong quake in the same vicinity this year. It follows a magnitude 7.8 quake in July.

Neither quake delivered a tsunami to the west coast of Canada, Washington, Oregon or California, but that possibility is always on the minds of people who know about the quake and tsunami risks around the Pacific Rim.

“There’s a clear history of events on the Aleutian chain and the Alaska Peninsula, so the Alaska Subduction Zone is very analogous to our Cascadia subduction zone,” said Harold Tobin, who leads the Pacific Northwest Seismic Network at the University of Washington and serves as the official seismologist for Washington State.

Washington is confronted with multiple tsunami threats. The Cascadia subduction zone runs from Cape Mendocino in northern California, past Washington, Oregon and Vancouver Island, Canada. Both what is happening in the Aleutian trench and off the northwest coast is a collision between the Earth’s crustal plates.

In both cases, the ocean plate, known in Washington as the Juan de Fuca plate and the Pacific plate under Alaska, are being forced underneath the continental crust called the north American plate.

Typically, those plates are locked together at and near the surface. But under tremendous and constant pressure they eventually slide creating what is typically large earthquakes. These so-called subduction zones, named for when one plate is pushed, or subducted below the other, create the world’s largest earthquakes.

What didn’t happen in Alaska in 2020 did happen on March 28 of 1964, when a magnitude 9.2 earthquake sent damaging waves into the Pacific and toward the lower 48 states. That included suspect sand layers at the head of Discovery Bay, where witnesses reported six feet of flooding from tsunami waves.

Washington, Oregon and California saw damage and death from the waves which rear up as the earthquake energy forced into the ocean water column reaches shallower water. Consider in Alaska, the U.S. Geological Survey places waves that ran up mountainous slopes 220 feet high.

We now have warning centers that kick into gear, as they did in both events this summer, that can warn that a wave is possible, coming or not a threat. In Alaska, a small tsunami of two feet was reported locally from the most recent quake. Alerts of a possible tsunami further away were soon canceled. Had that quake created a major tsunami, it would have taken between four or five hours to reach Washington state.

“We do have an advantage with these long-distance tsunamis, is that potentially you can get a whole lot of warning time,” said Tobin. "The tsunami warning center detected the earthquake, issued that initial tsunami warning. Fortunately in this case that could be canceled a little bit later on. But should it have been a big deal, we should have had several hours before it struck our coastal area.”

That is not true for people living near quake, either in Alaska or during a subduction zone quake off the Pacific Northwest Coast. When that happens the warning time is expected to be closer to 15 to 20 minutes. Washington, like Alaska has tsunami warning sirens to get people moving to higher ground as soon as the shaking stops.

But while much of the focus on warning times has focused on the outer coast, more recent research has looked to see if a Cascadia created tsunami would make its way into Puget Sound and other inland waters.

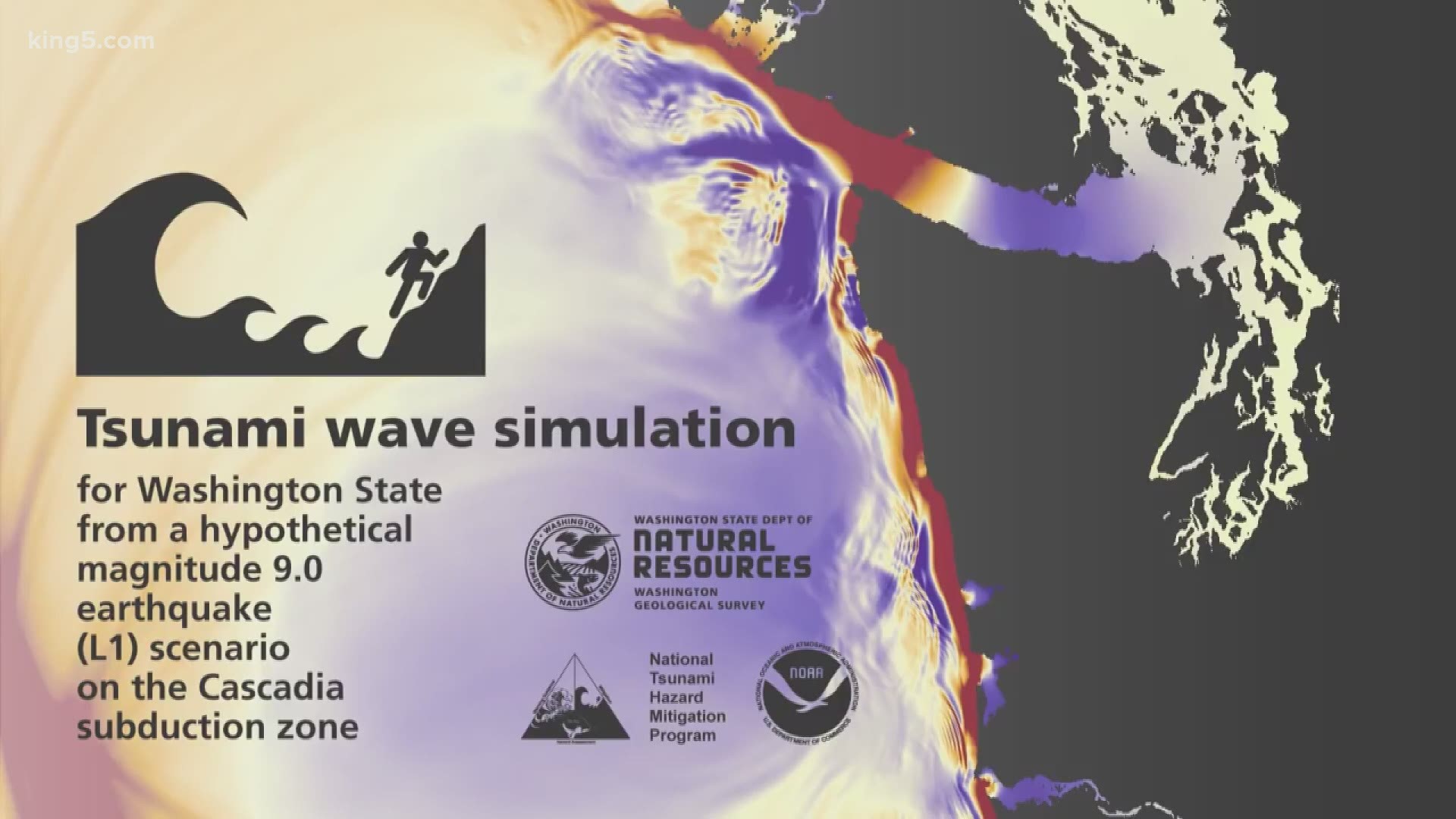

The Washington Geologic Survey, part of the Department of Natural Resources in 2019, assembled research it put into animations showing significant wave heights as far away as Tacoma’s commencement bay.

“Researchers all over the world are working on tsunami hazards,” said Casey Hanell, Washington’s chief geologist at the agency. “ As we get more information we are better able to refine our models.”

The use of lidar technology, to better understand the shape of the land, is helping determine the tsunami risk from rising waters and how those waves would travel.

Washington’s last great earthquake along the Cascadia subduction zone sent out waves so powerful they damaged coastal villages in Japan. While the magnitude 9 Tohoku earthquake in Japan of 2011 caused waterfront damage primarily in Crescent City and parts of Northern California, including one fatality.

Nearly every part of the Pacific Rim is on a subduction zone closely associated with tsunami generation. But while new research is showing inland Washington waters including Puget Sound where most people in the state live being more vulnerable than previously thought, DNR is considering the risk from long-distance tsunamis as well.

“Distant-sourced tsunamis are something we need to be aware of, they are a hazard for us in Washington, particularly our coastal communities,” said Hanell.

Fortunately, he says, most Pacific Rim quakes have not produced tsunamis that have had a major impact on Washington. And the 1964 Alaska quake was a standout, considered the second largest earthquake in modern history. It’s magnitude 9.2 punch coming in below a 9.5 in Chile just four years earlier in 1960.

The 1964 event also hit the west coast at a more oblique angle being centered more directly from the north in Prince William Sound. The angle of the tsunami’s origin may matter in their impact, making a larger quake way out on the Alaska Peninsula potentially more of a direct hit if the quake were more powerful. Also, the energy from distant tsunamis would be expected to diminish, according to Hanell making it less likely to drive the tsunami farther inland.

How far would a long-distance tsunami reach? We do know that waves reached the head of Discovery Bay off the Strait of Juan de Fuca in Jefferson County from the 1964 Alaska quake. The extent of just how far in more distant tsunamis reached is the subject of ongoing research.

Join KING 5’s Disaster Preparedness Facebook group and learn how you and your community can get ready for when disaster strikes.