The recent deaths of three Southern Resident killer whales have raised questions about what can be done, if anything, to save the dwindling pods. There are now just 73 southern residents left among the three pods that often spend summers in the Salish Sea.

A lot of attention has been focused on declining numbers of Chinook salmon, the residents’ food of choice, but scientist Dawn Noren says the problem is a bit more complicated. Other risk factors affecting the orcas' health include trauma from boat collisions, noise from boats, contamination from pollution, disease, and inbreeding.

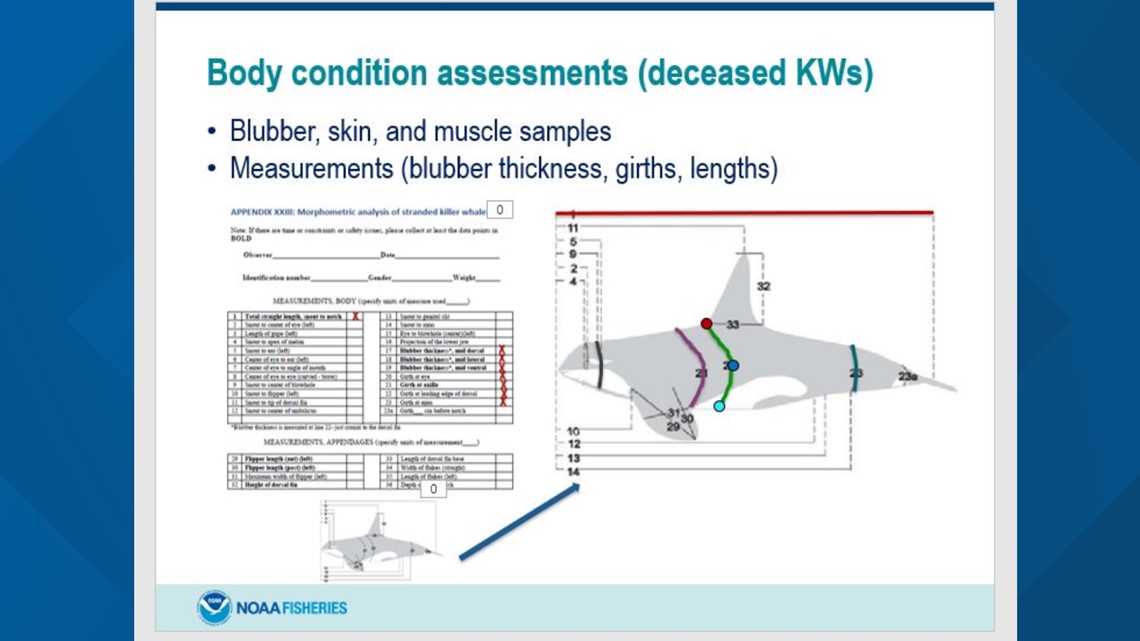

“We definitely should work on all of the risk factors. I don’t think we can easily dismiss one as a smoking gun right now given the complexity of how these risk factors interact, and also the difficulty of seeing a whale that is in bad body condition without taking any other samples and then actually figuring out what exactly is wrong with that animal,” explained Noren, a biologist at the Northwest Fisheries Science Center.

While the orcas may be emaciated, a lack of food is not the only problem contributing to their malnourishment. Sick orcas may not be able to eat or may not properly metabolize what they do eat. Noise from ships can knock the orcas out of hunting mode because they can’t echo-locate their prey.

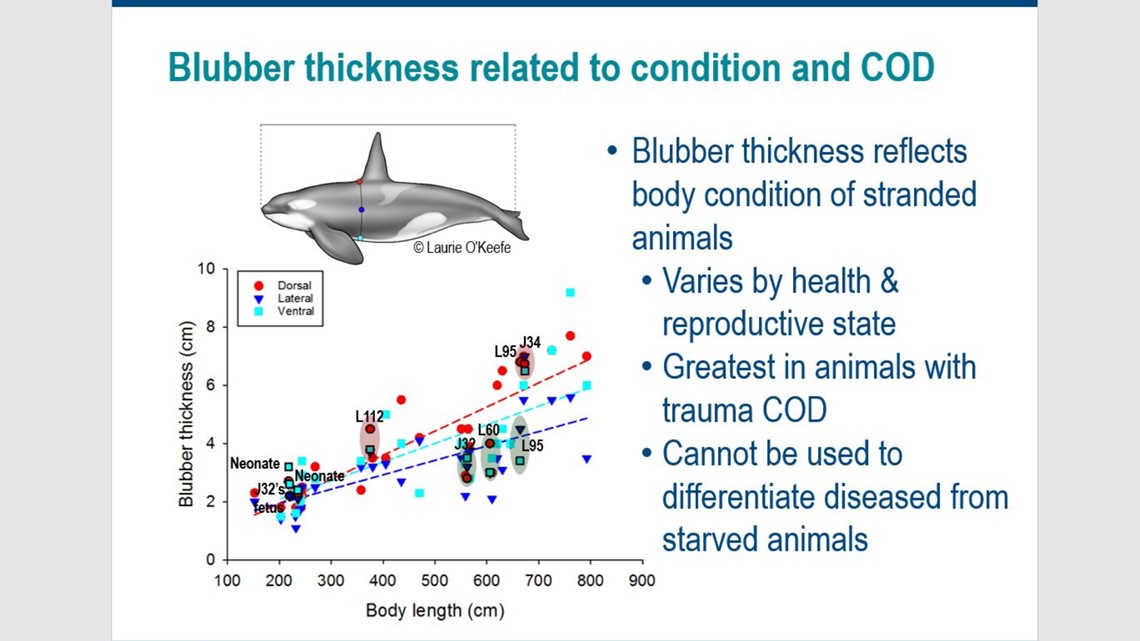

Less than 30% of deceased orcas are recovered for study. According to Noren, the Southern Residents that have been recovered did not die from starvation — they died of trauma from boat collisions, disease, or neonatal death, which is when a young calf just doesn’t make it.

A major contributing factor for neonatal death is the transfer of environmental contaminants from mother to calf. Noren explains that many of these contaminants — things like DDTs, PCBs, and PDES — are stored in fat and transferred to calves when they breastfeed.

“The dose of contaminants is the highest early on. So the higher doses the calves are getting are within the first couple months after birth,” explained Noren. The first couple months are also when the calves are most vulnerable.

Shrinking numbers in the pods also contributes to inbreeding.

University of Washington Biologist Deborah Giles has explained that the Southern Residents aren’t spending as much time in the Salish Sea because of dwindling fish populations.

According to the Center for Whale Research, orcas are also much less likely to reproduce when the fish supply is low, and 70% of their pregnancies already end in miscarriage.

Working to improve the salmon population is important, but the effort can’t stop there.

Noren summarized the problems, “If these animals aren’t getting enough calories, they will be more susceptible to illness. Also if they are highly contaminated, they are more susceptible to illness. Or if they’re inbred, they are more susceptible to illness. All of these things could be interacting in a way that we see these animals in bad body condition.”