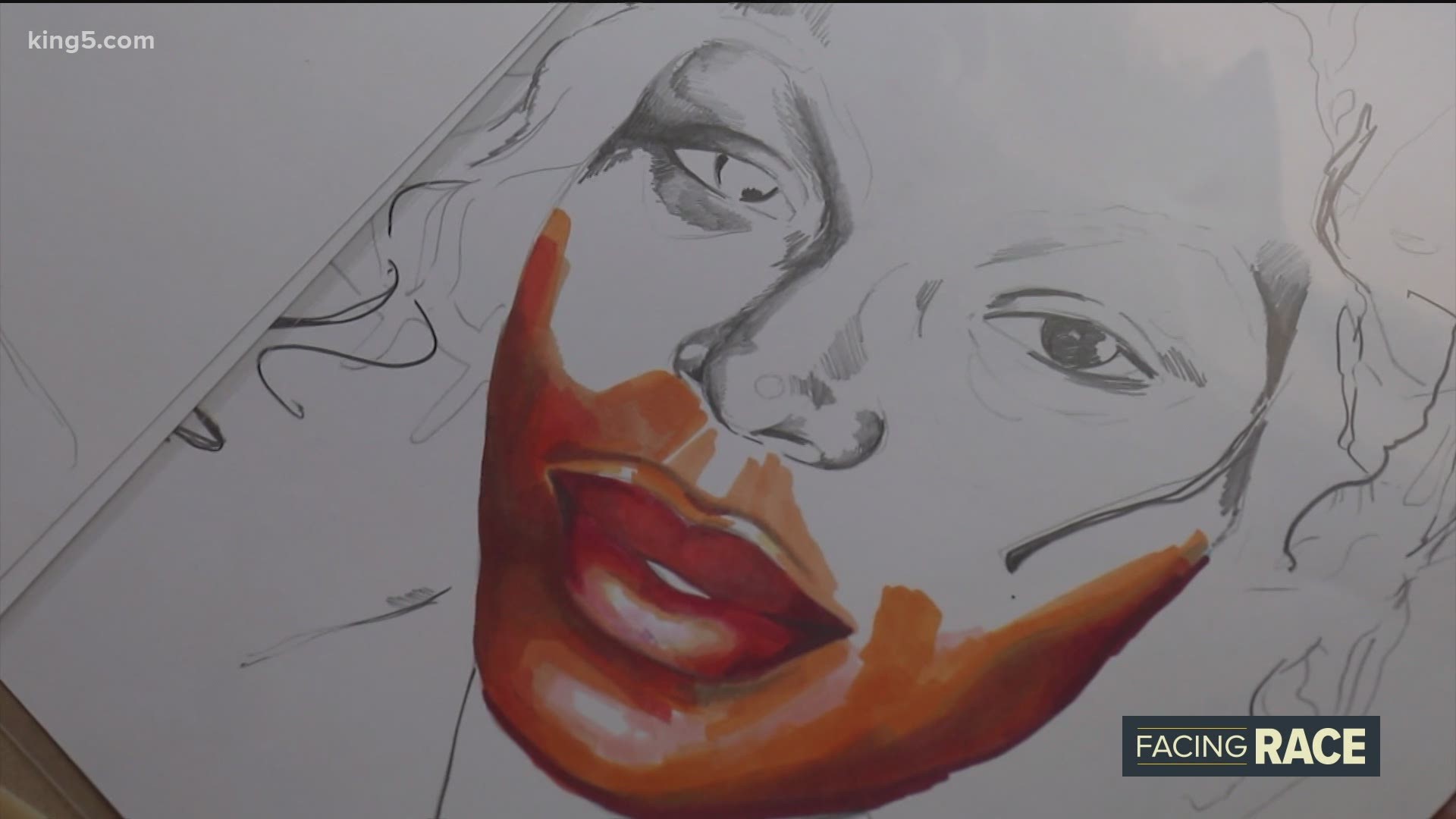

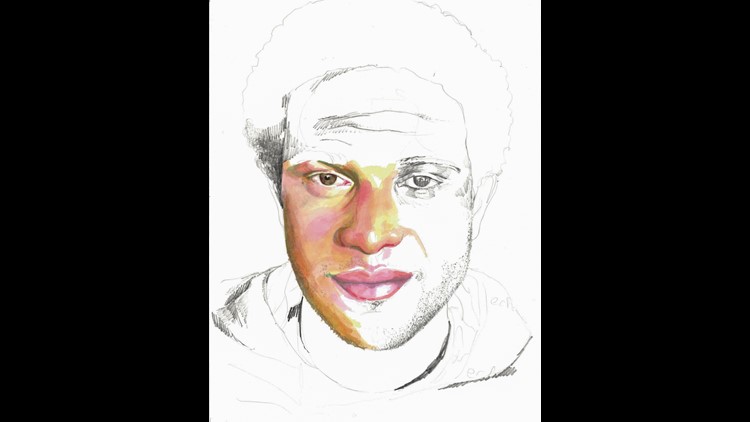

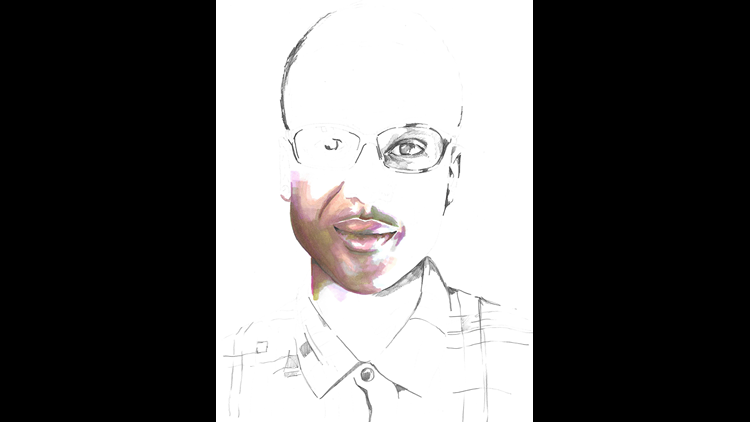

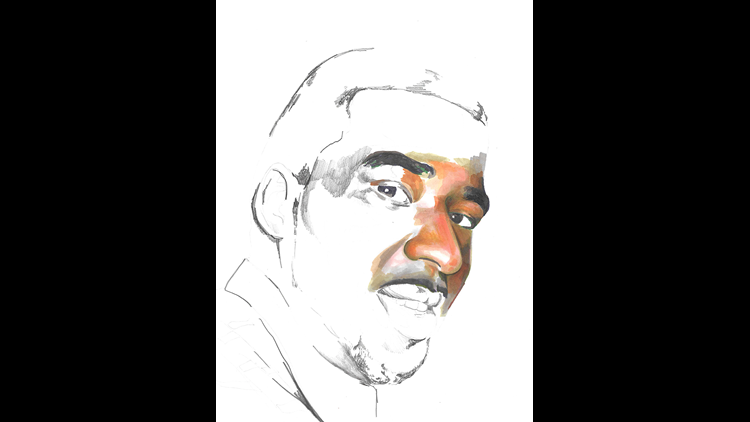

SEATTLE — From a makeshift art studio in his parents’ Seattle home, Adrian Brandon set a 20-minute timer in early August and went to work on a portrait of Giovonn Joseph-McDade, a 20-year-old who was fatally shot by a Kent police officer in 2017.

“I feel eager to start this piece — even though I know it won’t be finished,” said Brandon, as he stared at his light pencil sketch of Joseph-McDade.

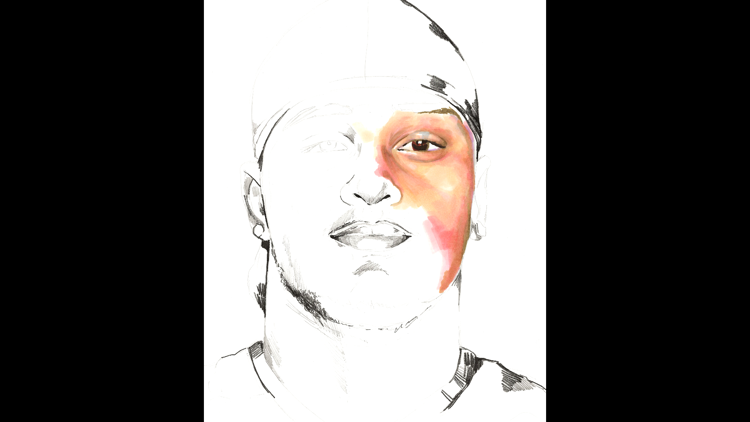

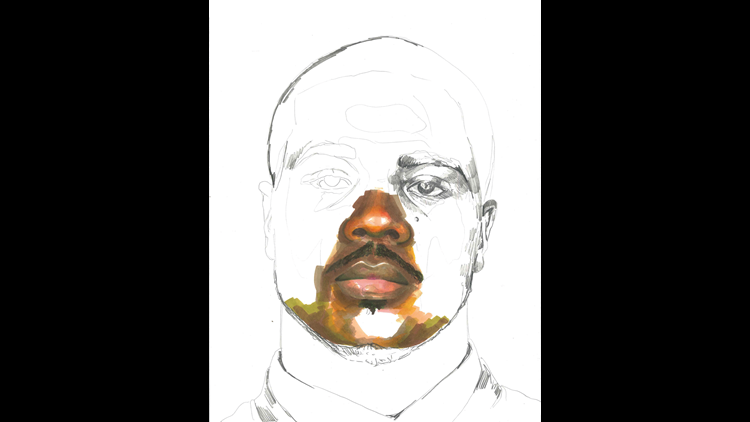

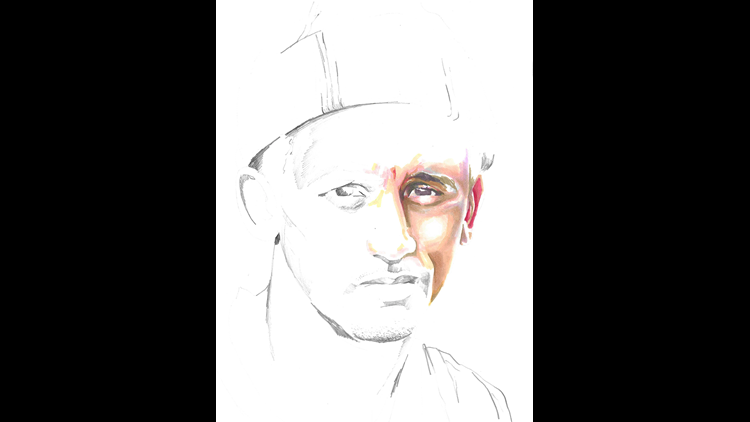

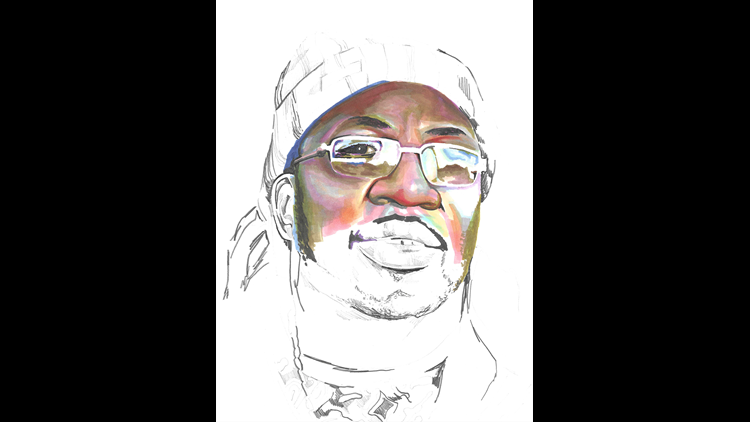

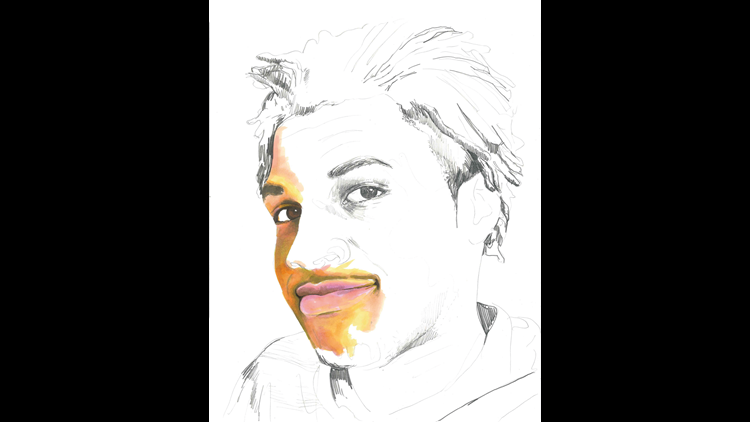

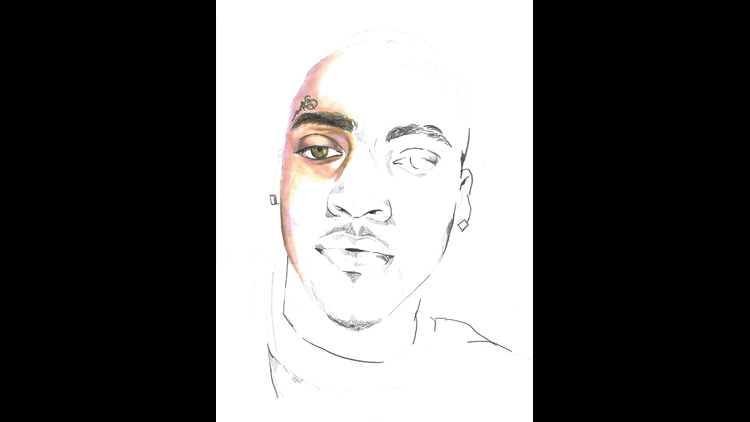

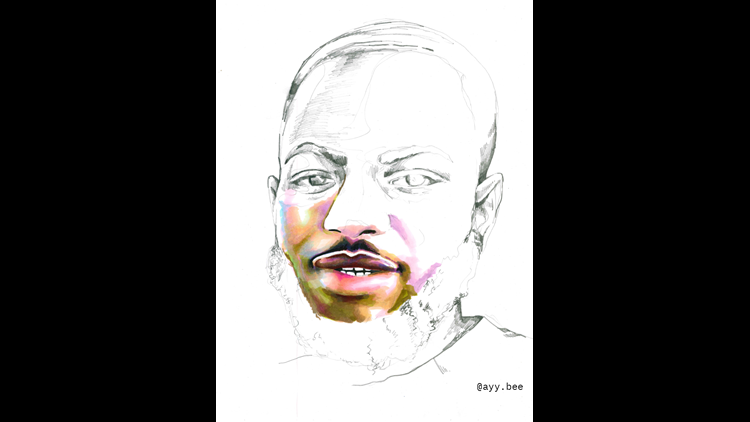

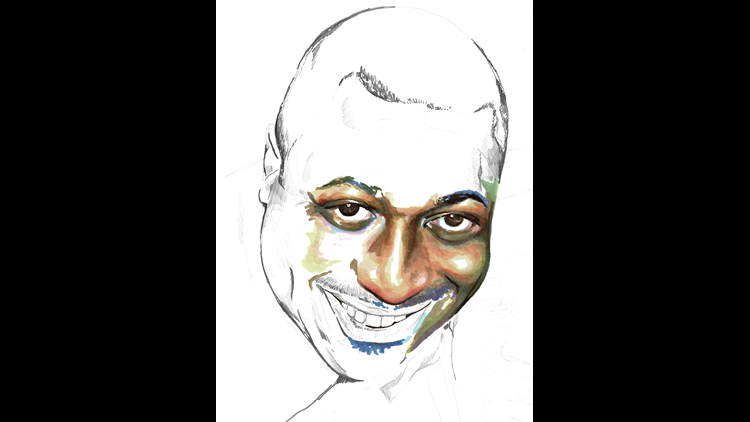

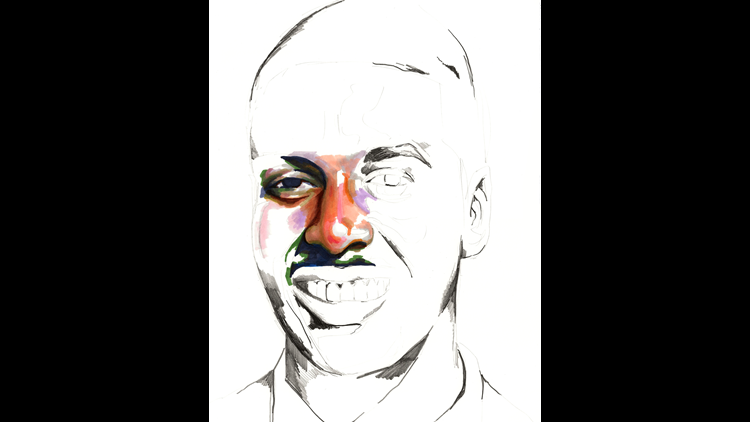

For 20 minutes, he colored in Joseph-McDade’s face; one minute for every year the Kent man was alive. Brandon finished coloring the man's right eye and cheekbone before the timer sounded. Then, he dropped his colored pens and used a pencil to darken the features he left black and white.

“I think the rough pencil sketch that I add at the end shows the underlay and the structure that this life was going to be built on,” Brandon said.

Brandon looked down and reflected on his unfinished piece. It was the 48th portrait the 27-year-old artist intentionally did not complete.

WATCH: Adrian Brandon's story

“It’s frustrating as an artist just to not be able to finish a piece, and then to realize that that represents something so much more intense and emotional in that it is a life that wasn’t complete,” Brandon said. “It definitely has led me to think a lot about my age and how close or far I am to each victim here.”

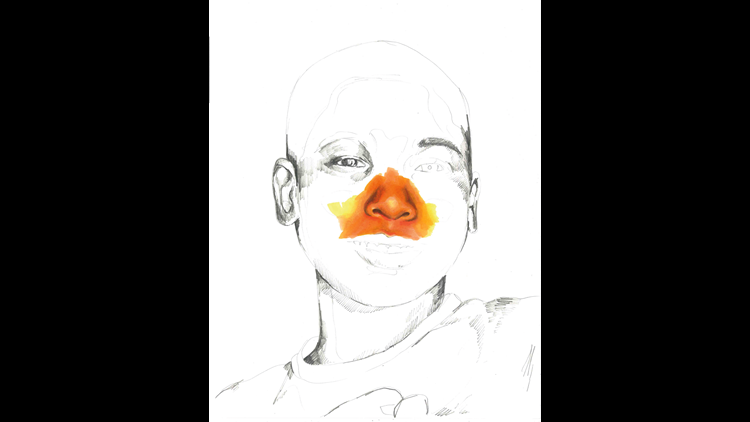

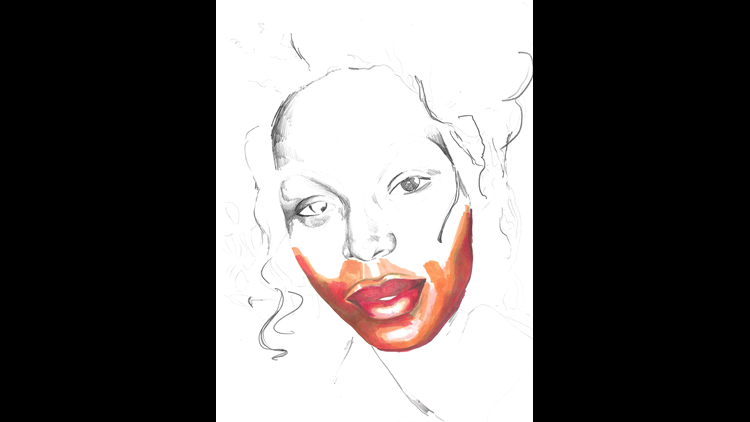

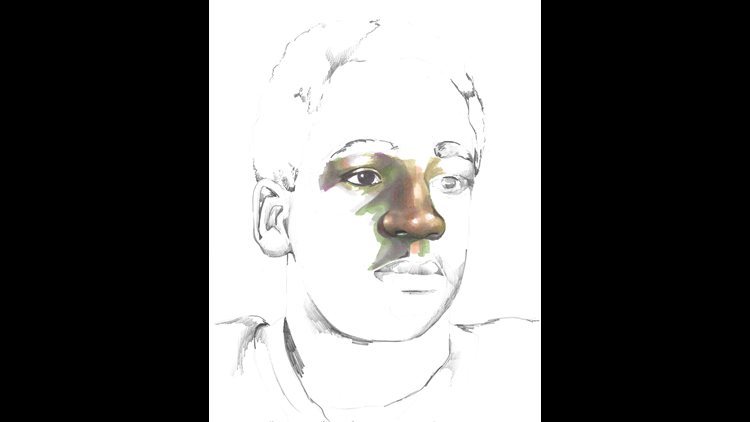

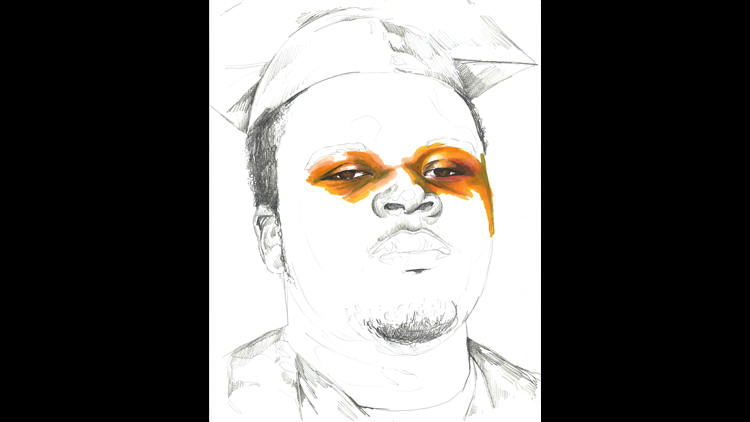

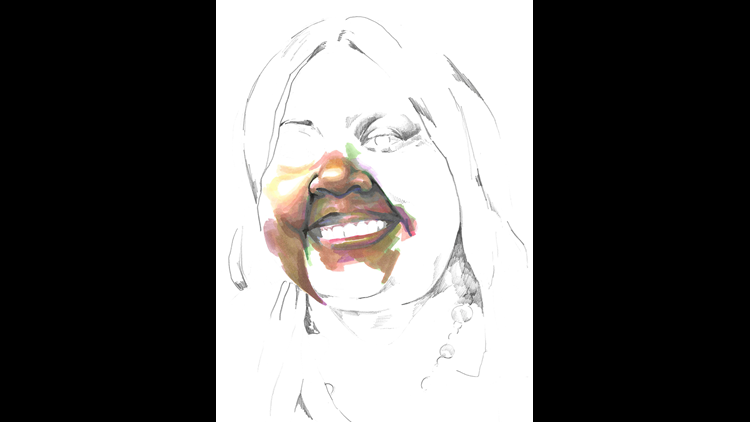

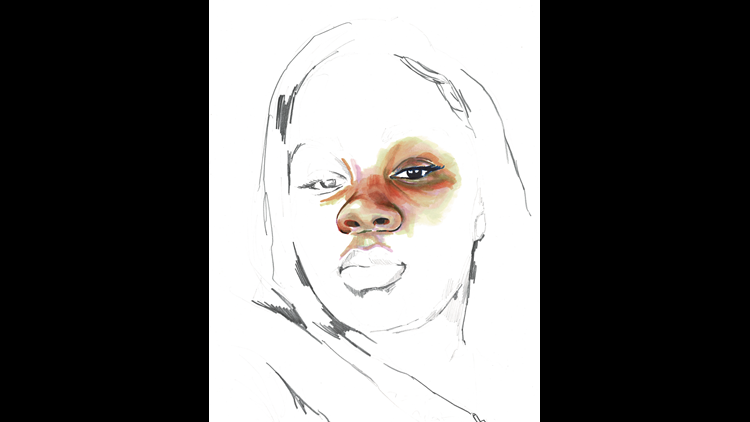

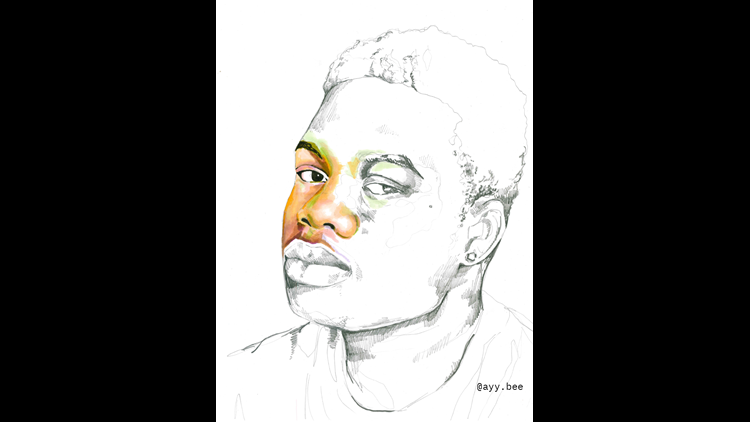

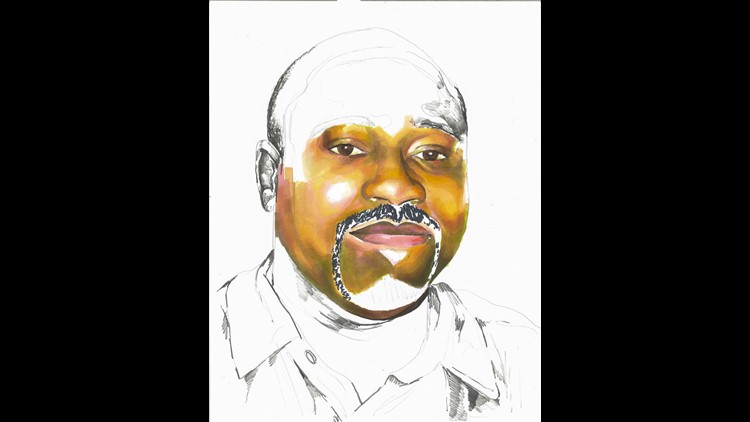

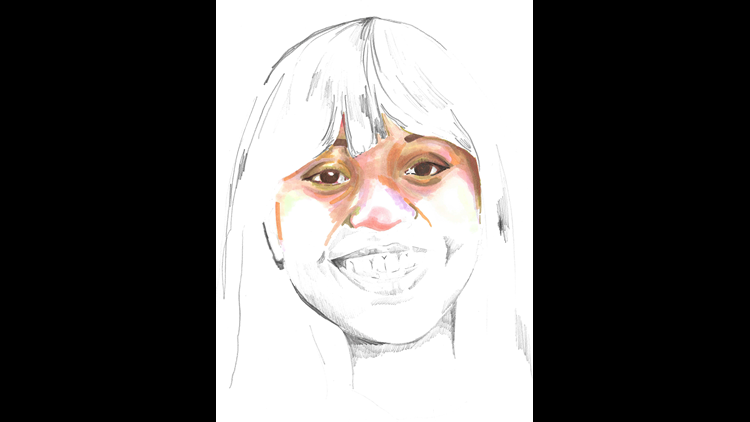

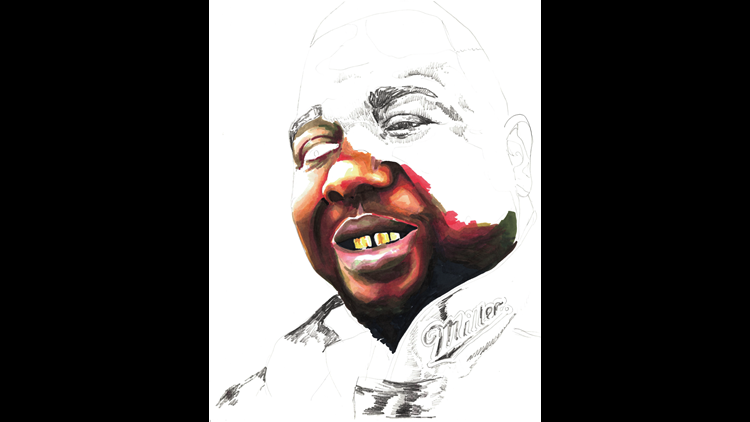

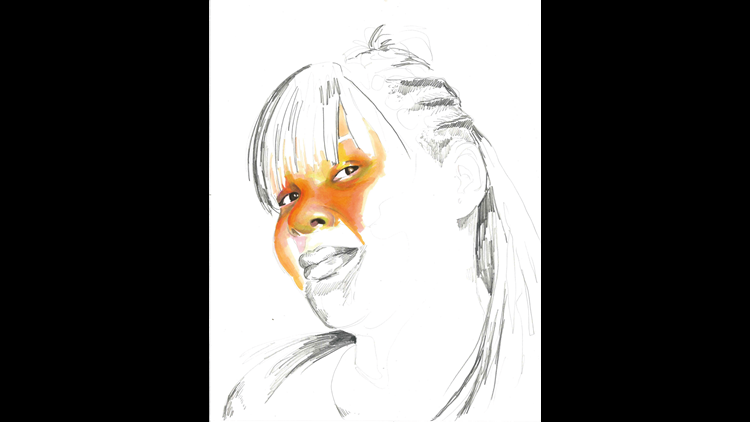

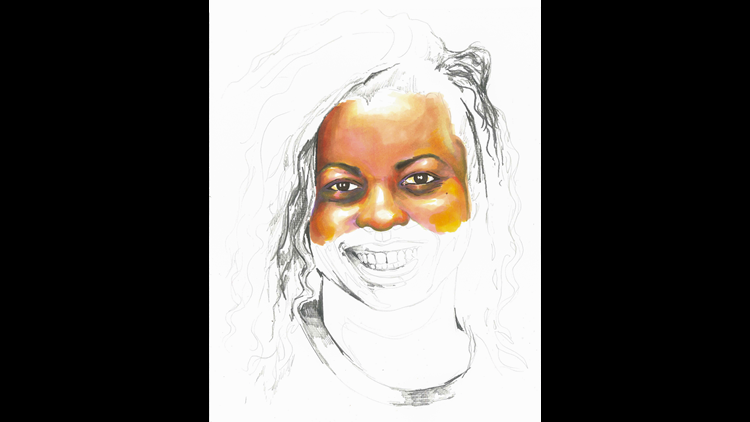

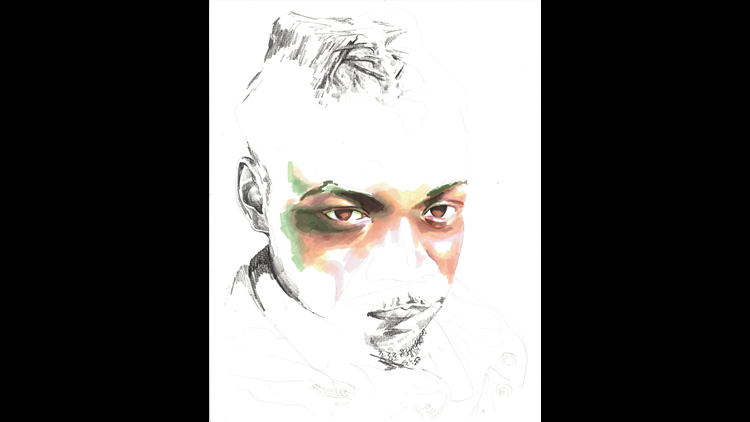

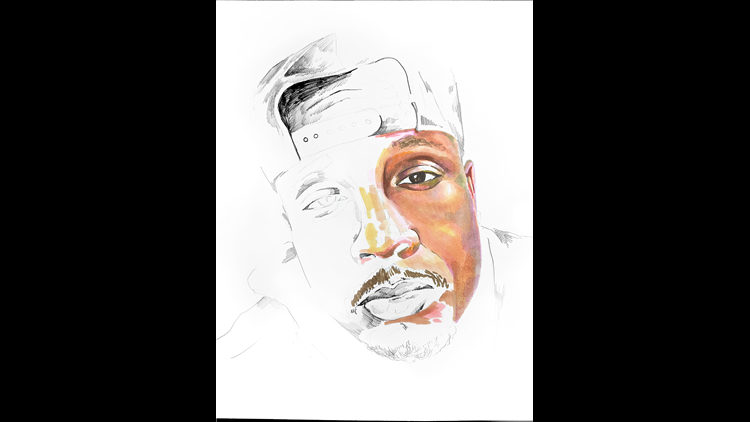

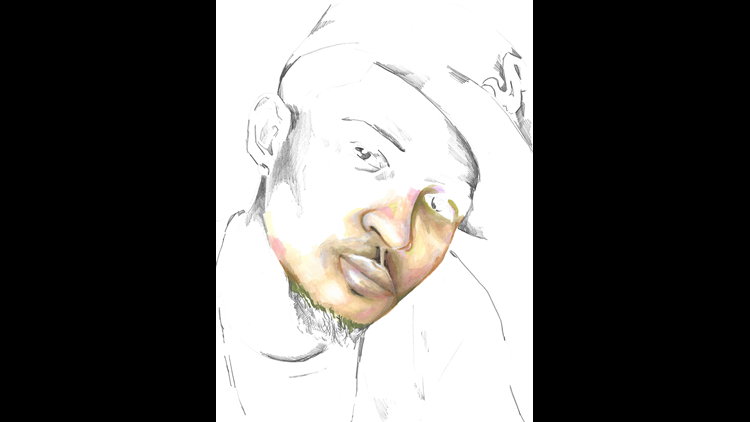

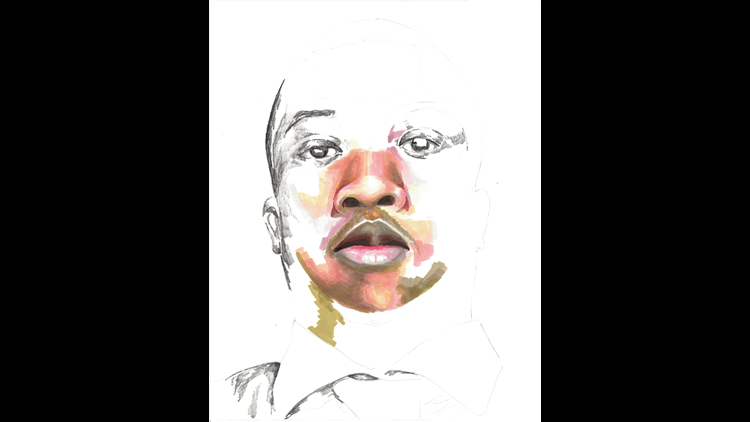

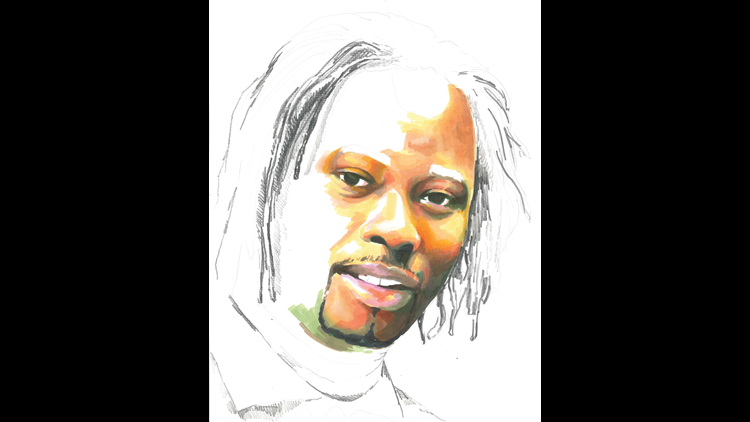

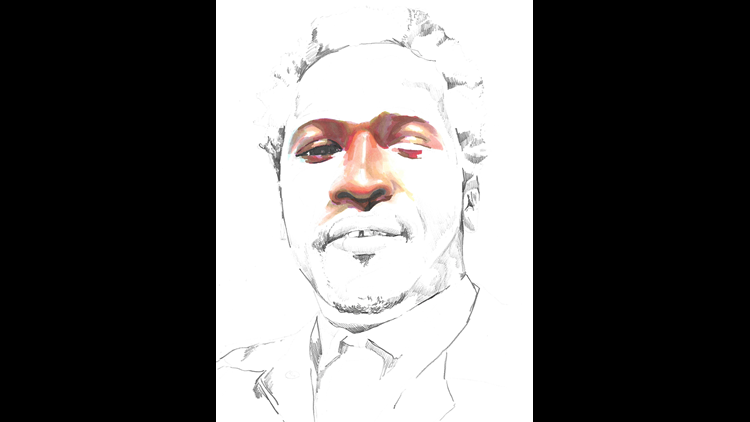

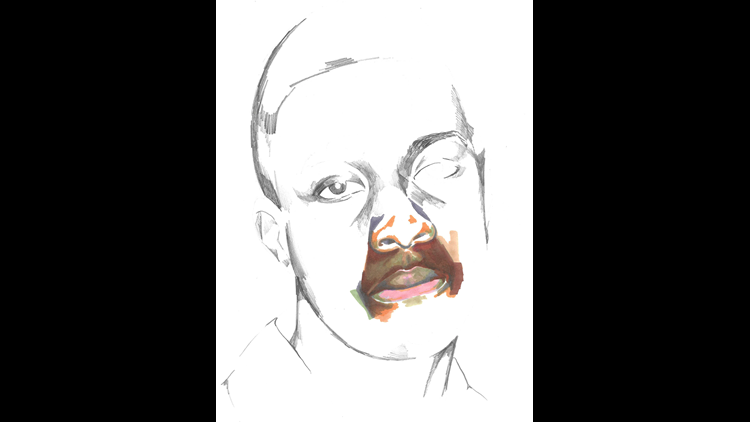

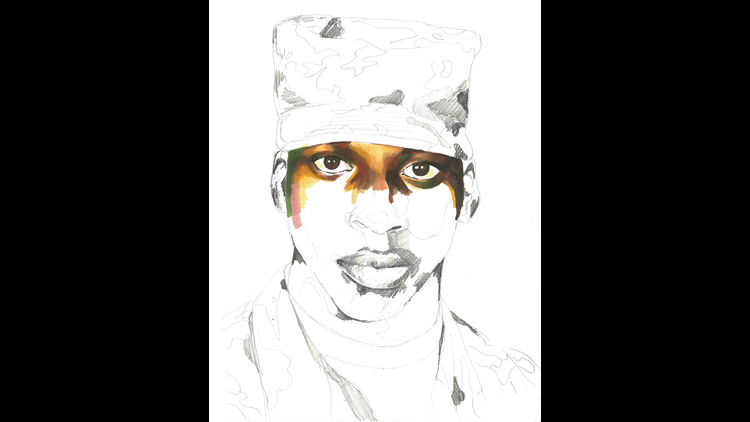

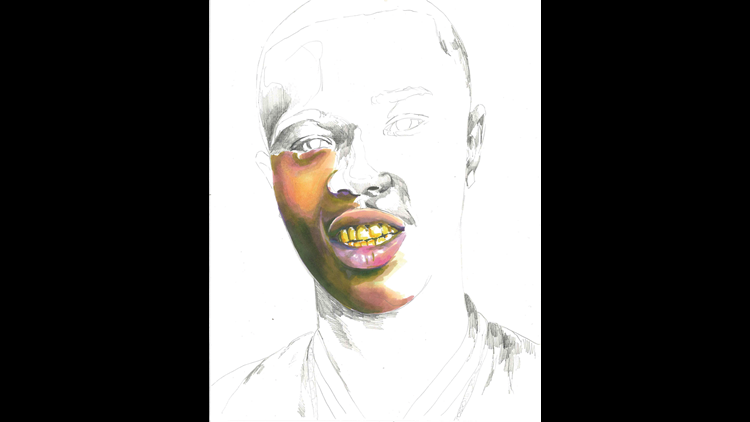

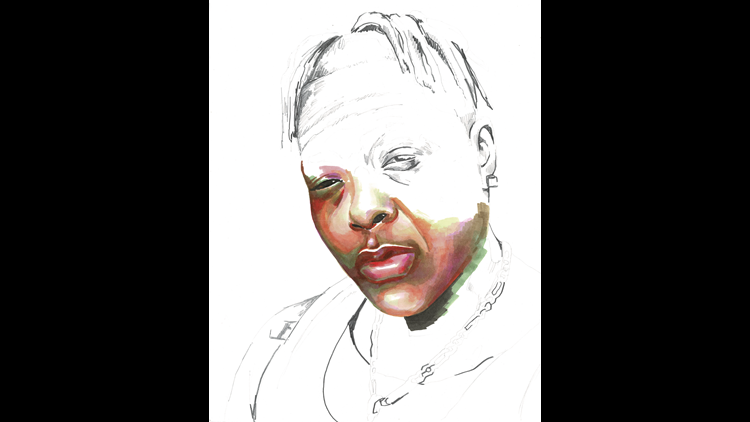

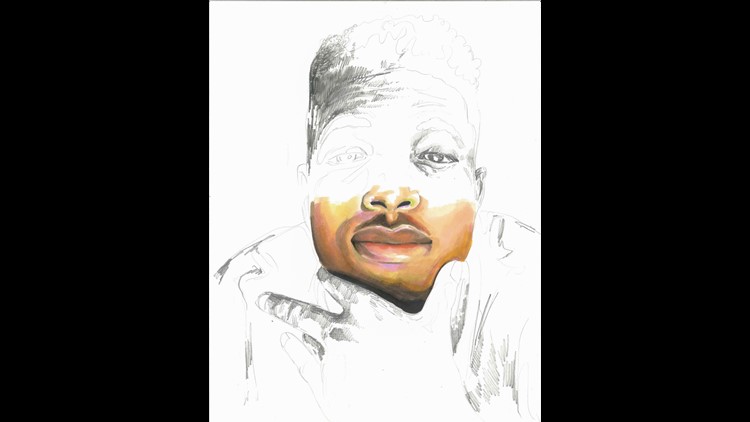

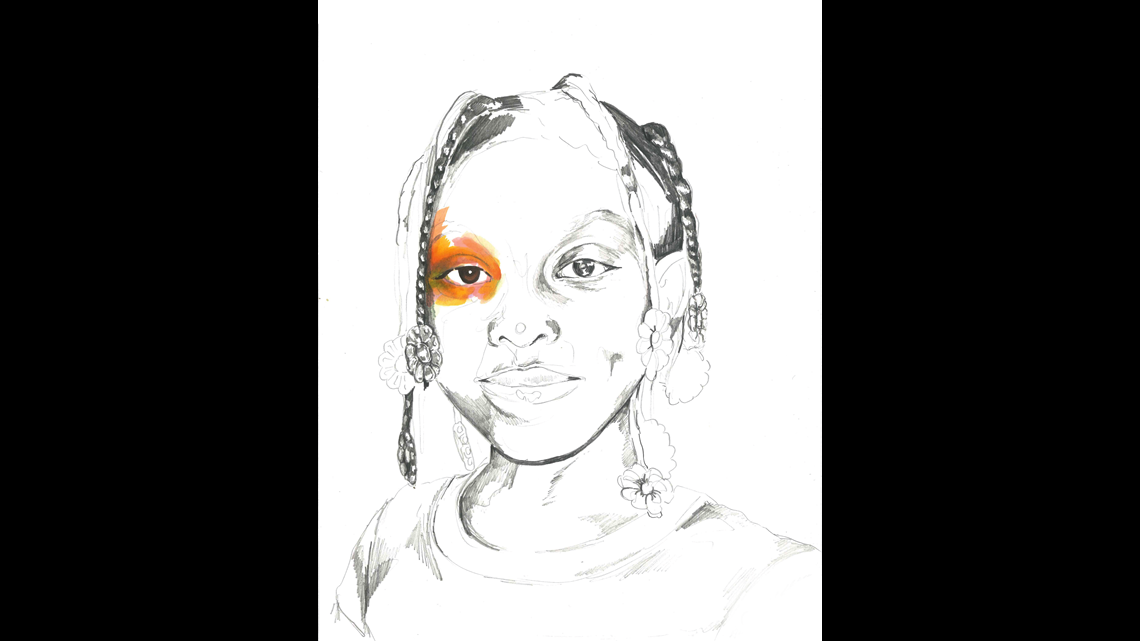

Joseph-McDade’s portrait is one of the latest additions to Brandon’s “Stolen” series, a project the Seattle-raised, Brooklyn-based artist launched in February 2019 to honor Black Americans killed by police. He uses time to define how long to color in each portrait; one year of life equals one minute of color.

“Luckily, a lot of artists do create these beautiful portraits of these victims, and that is really needed,” Brandon said. “I think it’s great to celebrate the lives they did have. But I really want to kind of show the lives that they didn’t have.”

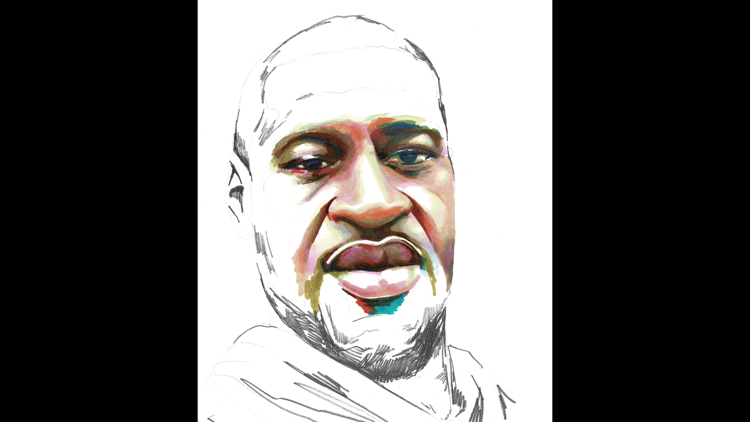

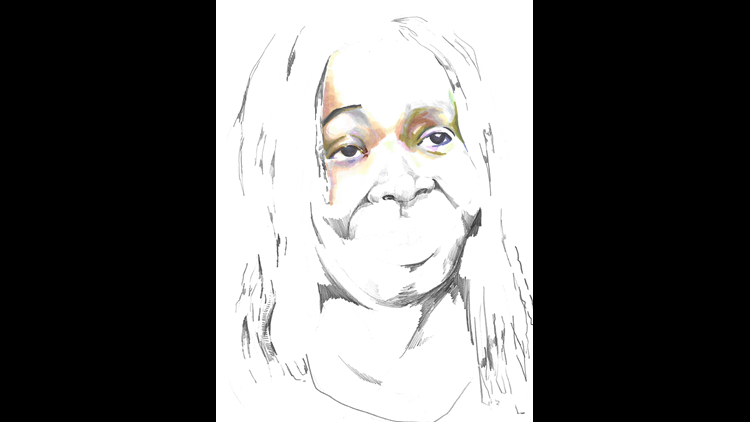

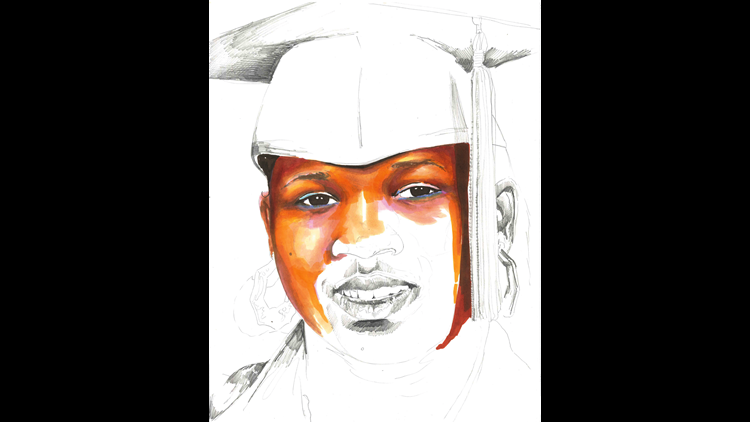

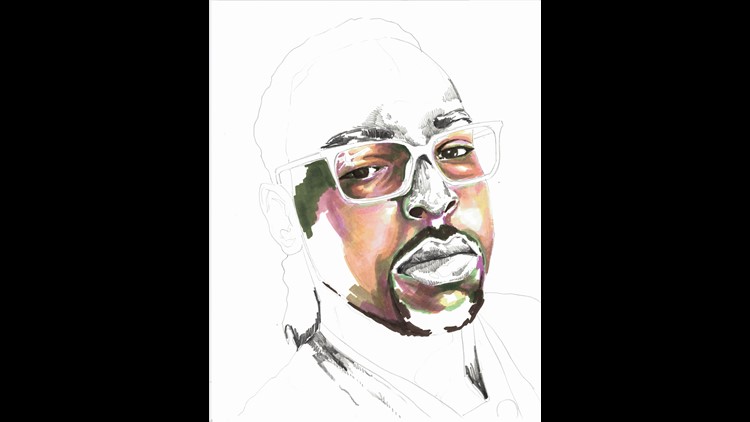

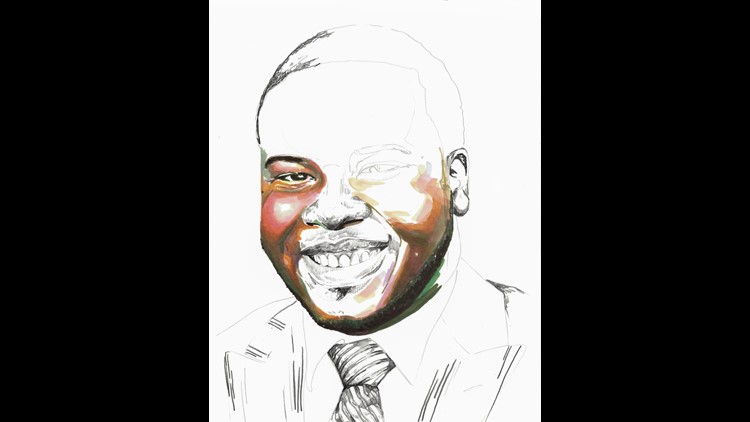

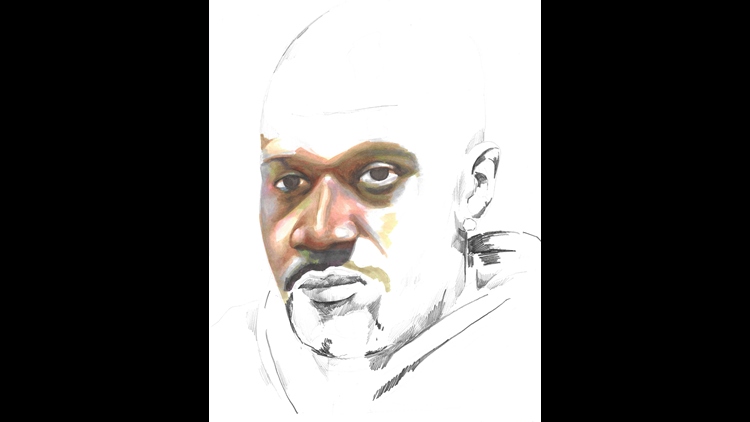

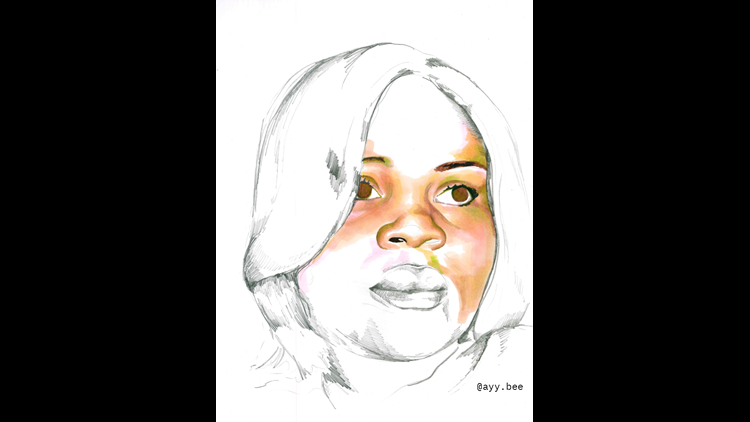

His collection includes portraits of people whose deaths have received nationwide attention, like George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Michael Brown. But Brandon makes a point to also draw other Black Americans, like Joseph-McDade, whose killings didn’t make national headlines.

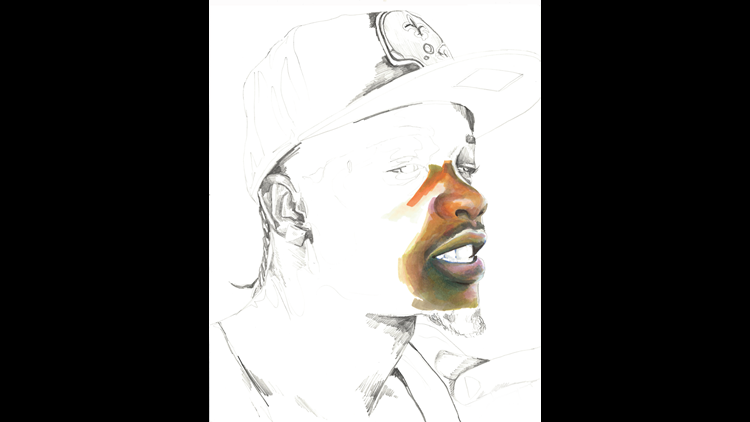

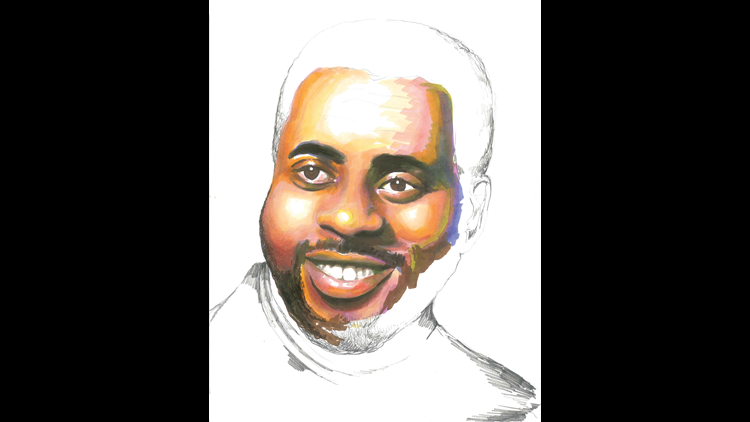

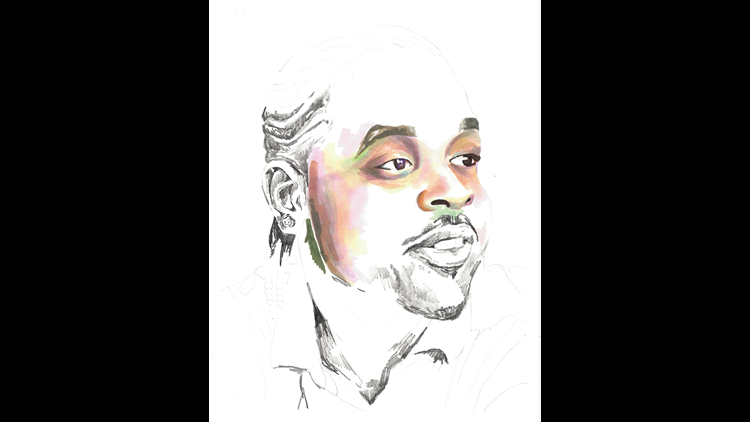

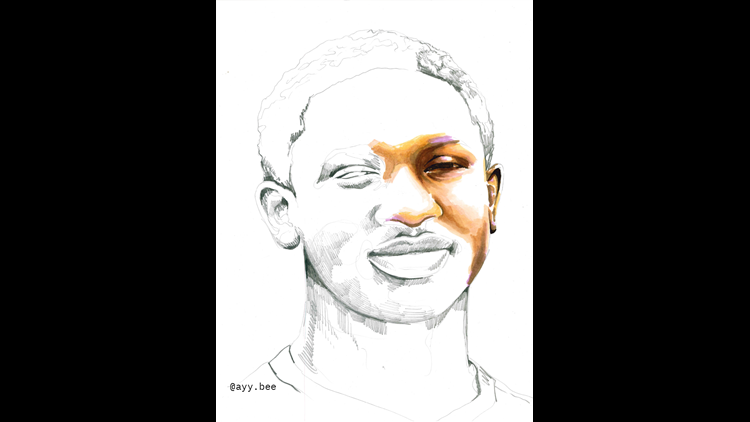

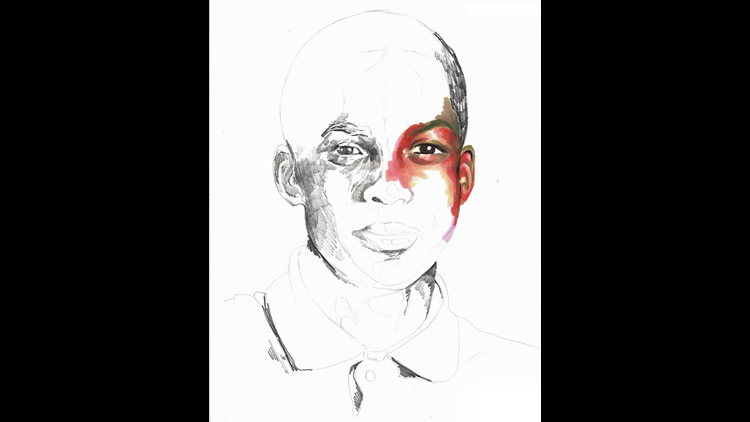

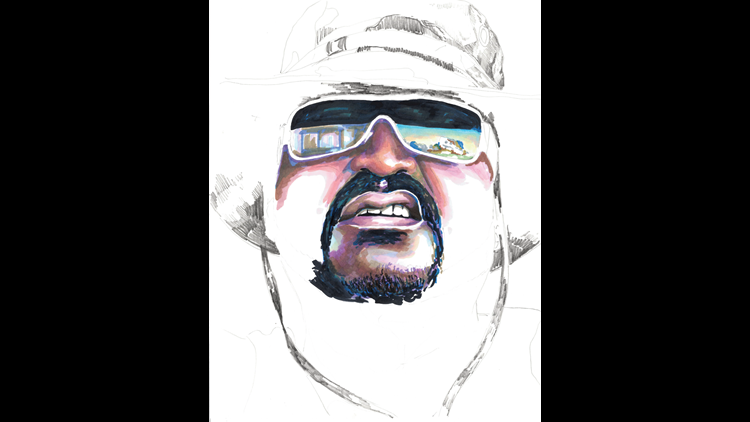

Portraits from the 'Stolen' series

“I’m learning about new names every day. People are sharing with me stories that are big in their community,” he said. “It’s cool to have a position where I can just help their voices be amplified, and hopefully those lives will get the amount of attention they deserve and hopefully result in some sort of justice.”

Brandon put on an in-person show in New York City last fall to showcase the artwork from his “Stolen” series. But earlier this year, his audience rapidly expanded after a Minneapolis police officer killed George Floyd.

Brandon’s Instagram account, where he posts each of his portraits, grew from 3,000 followers to 200,000. Well-known brands and celebrities, like actress Viola Davis, shared his work.

The Seattle native is back to work in Brooklyn after visiting his parents this summer in Seattle. But some of his artwork is on display in his hometown — hanging from the windows of an interior design shop in Seattle's Queen Anne neighborhood.

In an interview with KING 5, Brandon talked about the purpose behind the “Stolen” series and his hope for the future. He also revealed why time is a crucial part of this series in more ways than one.

Below is a portion of the conversation. Questions and answers have been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

How did you come up with the "Stolen" series?

“When I started this series, I was frustrated with how simple of a message ‘Black lives matter’ is. What we’re asking for: Stop killing us. These are very simple, clear things that we’re asking for. I wanted a way to visually represent that because for some reason, shouting that did not seem to get across to everybody.

I really just needed some other way for it to kind of click for people. I was just frustrated that the list was building and we were starting these hashtags, ‘Say his name?’ ‘Say her name’ but things were not really changing. We’re still seeing new footage of Black and brown people getting killed by police who were unarmed. So I was just trying to figure out another way to address this issue.

It blows my mind how people at all ages are still seen as a threat and as a target sometimes. That is what I really want to display. It is not just the 15-to-18-year-olds or 22-year-olds. I have someone who was 7 years old when she was killed. I have someone who was 43 years old. It’s a whole span, and that’s what I really want to get across is that you’re not going to outlive this. We’re always going to be Black.

What happens once you set the timer?

“Once I set that, I kind of push the timer to the side. I don’t look at it. That creates a sense of panic while I’m creating the piece—knowing that the time is going down and I’m not going to be able to finish the whole portrait. As I’m drawing, I’m feeling very anxious, kind of stressed out. These feelings are supposed to mimic the feelings that Black people feel living in America today. We’re not afforded the luxury to always be at ease when the cops pull us over or if we walk into a store and someone is following us... (It’s) really important for people to understand that (my artistic process is) kind of a performance in a way as well. It’s a very crucial part of the series.

How do you determine where to start coloring?

I select one feature that I think is unique to them. Sometimes it’s a smile, eyebrows, or an expression on their face or their nose or something unique.

In the beginning, when I set the timer, I always try to figure out how I can get as much of their face covered. I have this moment where I’m like, ‘Oh, let’s get to the nose. Let’s finish up the mouth. We can get to the ear and cover the eyes,’ just because it feels good to be painting in that way. It feels good to be covering the page. Knowing that time is of the essence, it is this weird sense of urgency to just give the portrait life. But I’ll catch myself and kind of dial back and remember that I think it’s more important to give each detail that I’m focusing on its proper attention and to not rush through the lips just to get to the nose. I should try to really focus on the lips and give it as much time as I would if there was no timer so that people can look at it and see the nuances of the face and see the finer details.

Tell us about the moment that timer goes off.

“Once that timer does sound, it always catches me by surprise, and it’s kind of symbolizing the end of their life. I’m left, you know, with this unfinished piece and the viewer is left kind of curious about what would more time have allowed. What would it look like if I did have 20, 30, 40 more minutes, two hours to complete the piece? That’s what families are left with. They’re left with, ‘OK, what was our son going to be? He was 18 when he was killed. Was he going to live out his dreams to be X, Y, Z?’”

How do you feel in that moment?

“It’s a range of emotions. I feel sadness, first and foremost. (I feel) heartbreak (that) that was it...

When the timer hits, it’s a way for me to grieve.... Giving each of these members of the series some of my time and my attention is really important because unfortunately we don’t have time. We’re still expected to work when we hear that George Floyd was killed or Trayvon Martin’s murderer was able to walk free. We still had to go to basketball practice. We had to pretend like everything is OK when inside we’re still hurting, and I really want to just bring that to light.

What I like about it, for me, is it keeps me active in researching these lives…. Just sitting down in a room by myself with a portrait of this person who was taken is my way of honoring (them). Just like so many other people in this country, it’s easy to lose sight of the scale and the long list so the fact that I can draw back on these experiences, and I have a photo and an image of a piece that I created for each of these stories does allow me to carry their story within me and hopefully educate others.”

How do you want people to react when they see your unfinished portraits?

“I want others to slow down when they see my work….I think it gets people thinking…

When you look at each piece, you don’t know that they love to play football. You don’t know these personal defining characteristics. But you’re left wondering what they could have become. I hope that people look at (the portraits) and do research….

That’s the whole point of this -- for them to see these faces and say, ‘First of all, why isn’t the face covered?...Where are they from? What did they like to do? How did they get killed? What happened to the people who killed them? Oh, they’re still working? How is the family doing?’ These are all of the questions I want them to cycle through. ‘Why don’t I know about this person? Does my family know? How can I tell others this person's story?’ I think the emptiness really leaves room for that. That’s something I’ve developed an understanding of the more I’ve worked on this. I think that’s what’s cool about this series is I’m constantly learning about it and learning its potential and its power.”

What’s the hardest part about the "Stolen" series for you?

I think the hardest part about the series is just the number—the sheer number — the fact that I’ve done (more than) 45 pieces, and I still have 30 that I know of to do. Knowing that I could continue to do this series for 20 more years, it feels never ending. That is the same feeling that I think a lot of people are struggling with. We’ve been in the streets for a very long time, and it feels like very little progress has been made. I think it’s this darkness that comes over me when I really focus on producing a lot of portraits. I have to take a lot of breaks because I lose hope, and it’s really easy to do so when I’m realizing a kid was killed at 15 years old for leaving a house party—Jordan Edwards—and that could have been me. That could’ve been my brother and my cousin. I see a lot of myself in the pieces, and that’s what freaks me out. I just need to give myself time and be patient with myself because it does feel like a lot to carry for an art piece, for sure.

Why do you see so much of yourself in the pieces?

I see myself in physical ways— the ways that people carry themselves, the styles that they have in the photos that I’m using, in the colors that I’m using, in the complexion and the layers and just kind of their features. I will literally see myself in some pieces. There’s (a portrait) of a man, Manuel Ellis, that I just finished recently, and the way he had his hat positioned, the same facial hair, all that, and his eyes kind of mimicked mine in the photo.

Let’s talk about your background as an artist. Have you always tackled race as your subject?

Yeah, ever since I got serious with art, it always revolved around race….

(Art) was a great outlet for me in high school. Being someone who is mixed, someone who is Black at a predominately white private school in Seattle was tough....I felt like I represented all Black people at the time because they, my friends, didn’t know anybody else really. I was one of two or three Black boys from sixth grade through 12th. It was tough, and it weighed on me…I was trying to figure out my own sense of identity, and art kind of allowed me to explore and share my perspective a little bit more so than I could with words. I loved it being an outlet, a form of therapy.

And then as I graduated and went to college, I used it more so as a tool for change and to address issues that I’m really passionate about….I love that my art can be a way to connect with others outside of my race. If it will help people understand situations better and my experience or my community’s experience, then I think that’s a great place for me to be.

What are you expressing when you put your art into the world?

I really try to capture the full Black experience. Obviously, every Black experience is wildly different, but I think there are some common threads there. With the “Stolen” series, it really addresses the pain and the suffering and the injustices that we’re facing today. What I love about my art and art in general is that it’s from the heart, and I think it really shows the humanity in people. I think that’s really, really important. We need the policies to change. We need legislative change as well. But we really need just people, individual people, to have that mentality switch and open up their mind so that they’re more receptive to changing their ways and calling themselves out and calling their friends out. I love that art is a crucial role in this movement.

What is your ultimate goal for the series?

The issue that we’re trying to address is obviously complex. But it’s very simple in nature in that we just wanted to be treated the same, and so, I wanted to create art that was very simple to digest....I think art is such a powerful way for people to communicate with one another. It transcends language barriers. It transcends age differences. It’s something everyone can digest and interact with.

I just hope people start talking about it. I hope that it just creates a dialogue. I’ve received countless messages from people that have already done so, and they’re saying, ‘Hey, I never talked to my grandparents about race, and I showed them your art, and for the first time, they opened up, and I got to express what’s on my mind and they shared their perspective and it was a really beautiful moment.’ Or teachers will reach out from across the world, and they’re saying, ‘Hey, I want to show my kids, my students your work and show how art can be this whole other side of activism that they haven't explored yet."

This story was produced as part of “Facing Race,” a KING 5 series that examines racism, social justice and racial inequality in the Pacific Northwest. Tune in to KING 5 on Sundays at 9:30 p.m. to watch live and catch up on our coverage here.