SHELTON, Wash. — 911 calls captured the desperate pleas of Taylor Krise and his family on Nov. 23, 2020. His brother, Derrick Wily, 27, had been missing for weeks. The last person to see Wily alive had just confessed a shocking secret to his family.

“I need the police here right now at Lake Isabella," the 911 caller said. "They are taking us to Derrick’s body. I’m really scared."

Despite their urgent appeal, the Wily family said police help was slow to come.

“Now, get cops out here now! Before somebody kills again," Wily’s sister-in-law told 911 dispatchers. "Goddamnit!”

Before the night was over, Wily’s family would find his dismembered remains and come face to face with his killer.

Those who knew and loved Wily are still stunned at his brutal murder.

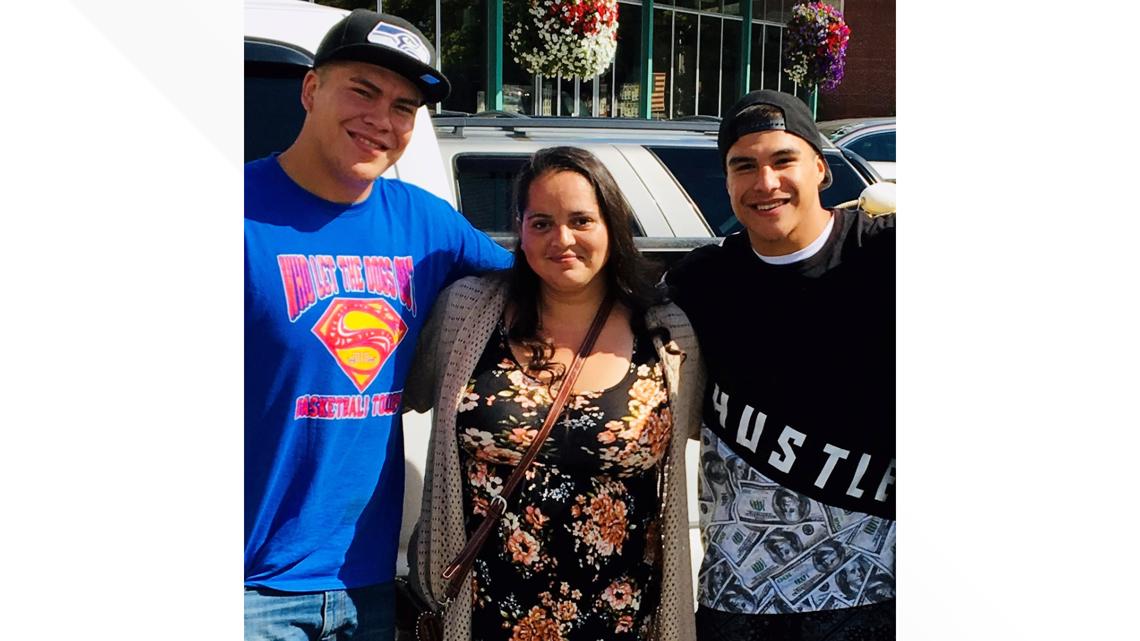

“He was just a funny kid, and just sweet,” said Malynn Foster, Wily’s foster mother. Foster raised both Wily and his brother Krise from the age of 11. “He's the only one of my kids that ever asked me to be his mom. Not very many parents get to experience that, you know, to have your kids actually choose you.”

From all accounts, Wily had a difficult childhood in several foster homes. Foster said Wily had many of the same troubles other Native children have when growing up in the foster care system.

“Just thinking that violence was okay," Foster said. "Drug and alcohol problems, really all comes down to a lack of being okay with being a Native because of not having a positive Indian identity."

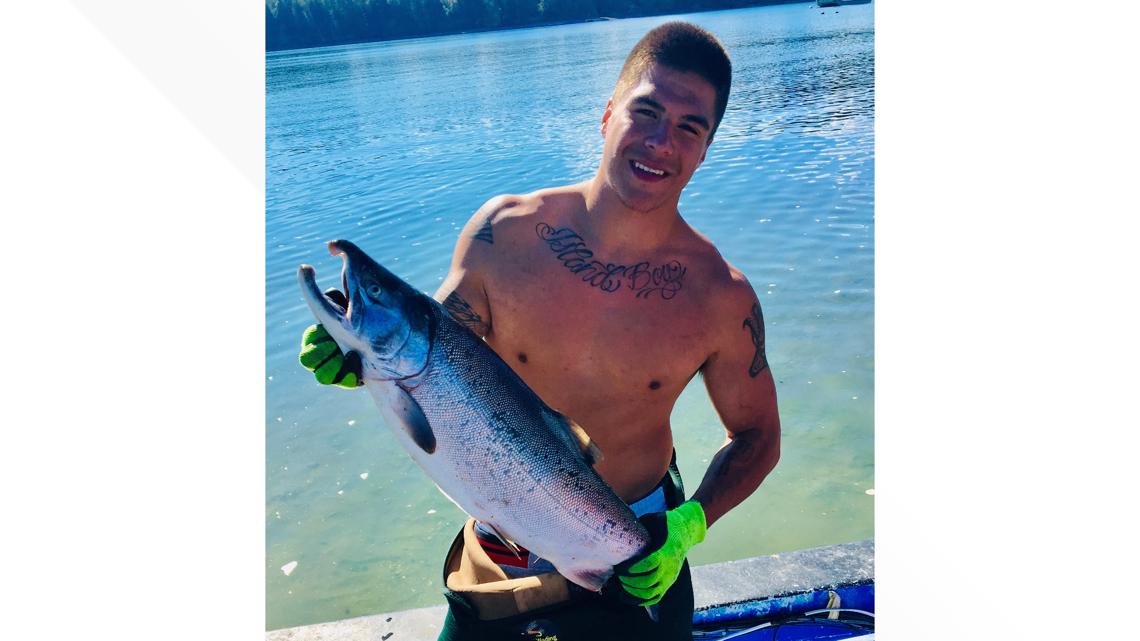

But as he grew up, Wily excelled as an athlete and played football. He was in and out of trouble with law enforcement but remained close to his family and young relatives.

“When somebody said he went missing, I knew something was up. Something, something bad happened,” Krise said.

In early November 2020, when his family hadn’t heard from him in several weeks, they decided to go to the police to file a missing person report.

According to dispatch logs, the Mason County Sheriff’s Office initially did not take the report, saying there wasn’t enough information and Wily was an adult.

“I wasn't surprised by it," Foster said. "Because I know it's a systemic issue for people."

Statistics show Native men make up 75% of all Indigenous homicide victims.

“Our men, they're missing and murdered too," Foster said. "It seems like they keep being just left out of the conversation."

“They're always talked about in the deficit," said Abigail Echo-Hawk, with the Washington State Task Force for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women & People. "It's also asking, ‘Well, were they drinking?’ Are they an alcoholic? Are they a drug user?' It is a common story for police departments to not take the missing persons reports of Native people.”

“That’s why our people have become experts at finding our own,” Foster said.

With no police support, that’s exactly what Wily’s family did: they launched their own search.

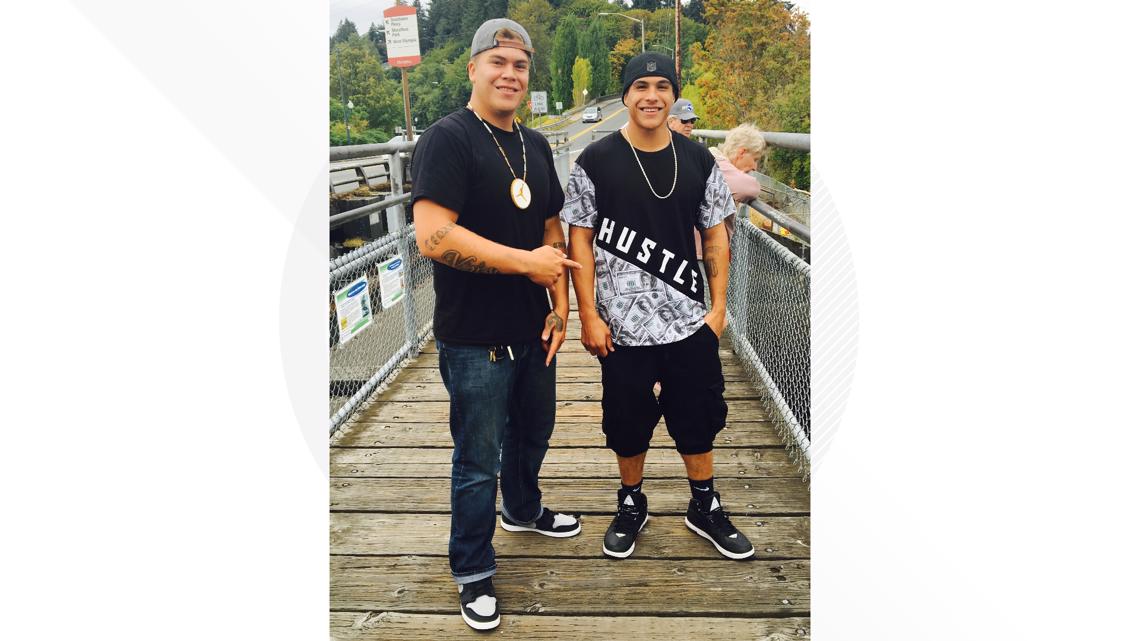

Krise started by tracking down the last people who saw Wily before he disappeared: his cousins, Jordan and Jareau Afo.

Krise went to the Afo home in Shelton, hoping to find clues about where his brother was. Maybe they knew something important.

Instead, he said he got a confession about the worst possible outcome.

“I just asked (Jareau), I was like, ‘Where is he?’" Krise said. "Then (Jareau) gripped my hand and he said, ‘I killed Derrick. I killed him.’ Everything just kind of went numb. Everything just kind of went cold."

Shaken, Krise went to the Shelton Police Department for help. KING 5 obtained the videotaped statement Krise gave Shelton police detectives, detailing Jareau Afo’s confession.

“He's like, ‘I just choked him,'" Krise told detectives. "I said, 'He's for sure not alive?' (He said,) 'Oh, he's not alive, man. He's not alive. I know he's not alive.' I was sitting here looking at the eyes of somebody who just took my brother's life.”

Wily’s family said they begged Shelton police for help in recovering his body and arresting his confessed killer. But that help was slow to come.

“I said, ‘You guys need to get over there," Krise recalled saying as he left the police station. "Now."

Shelton police did not jump into action, as Krise had hoped. Shelton Police Chief Carole Beason said jurisdiction issues held them back.

“We reached out to Mason County Sheriff's Office and said, ‘Hey, this is the information that we have,'" Beason said. "We immediately notified them, but it's their jurisdiction."

Wily’s family was shocked to later learn the Shelton detective that took Krise’s statement and would eventually take lead on Wily’s case had no prior homicide training.

“It's not required," Beason said. "It's simply considered specialized training, advanced training, but it's not required to do an investigation. I got to tell you, they, in my opinion, they did a good job on this investigation.”

Into a nightmare

On their own again, the family continued their search to find their brother by convincing Jordan Afo to drive them to Wily.

Jordan’s behavior was erratic, and he seemed intoxicated. Yet Wily’s family was desperate for answers.

Jordan took the family to Lake Isabella State Park and led them to a fence bordering a nearby junkyard.

“When we got there, [Jordan] just turned around and stopped," said Casey Brown, Wily's oldest brother. "He was standing on this plank that was going across the swamp. And he said, ‘[Wily’s] head is right there. It's buried in the, in the swamp.'"

The family’s grief at this moment is captured on audio recorded by the family.

“How could you do this? What is wrong with you? I can’t believe this. Just stop…I can’t see Derrick man, I can’t see him. They butchered him.”

The family’s cries reflect a sobering, sad reality for many Indigenous families.

“I know that that is pain that has been amplified as a result of the lack of resources of the way that [the] family was dismissed, and the way that [Foster] has continued to struggle to get justice for her son," Echo-Hawk said. "No mother deserves that. No family deserves that. And yet it is the common experience of Native people in this state and in this country."

Now, face to face with Wily’s killer and standing next to eight garbage bags filled with his remains, the family once again called the police for help.

“We tried to get somebody to come out here with us,” Bobbi Brown, Wily’s sister-in-law can be heard telling a 911 dispatcher.

“I wish you guys would have waited for law enforcement to get there before you did this,” replied the dispatcher.

“But then it might not have been, it might not have happened,” Brown said.

Roughly two hours after Jareau Afo’s confession to Krise, body camera video from Shelton police shows officers finally arriving and relaying details about the crime scene to command staff.

“Hey, there, so the family took me to the spot," an officer can be heard saying on police body camera video. "I can't see the body. He’s somewhere under these logs. [Afo] hid him in the little water area on the backside of the junkyard. No, I'm not touching it. We’re not really looking, we’re waiting for the crime lab to get here. He’s in pieces out here.”

Jordan and Jareau Afo were arrested that night.

In December 2022, the Afo brothers pled guilty and accepted a plea deal for their roles in Wily’s murder. Police believe Jareau strangled Wily to death during an argument in the Afo family garage. Jordon confessed to dismembering and dumping Wily’s remains after the fact.

Jareau was sentenced to 20 years in prison and Jordan received a five-year prison sentence.

These days, Foster’s grief has a physical form. Foster and her son Krise are both accomplished Coast Salish carvers.

“'Mourning Prayers for our Missing and Murdered' is one of the stone sculptures that we just had installed,” Foster said of two large stone carvings that now greet visitors at the entrance of Seattle’s newest Convention center.

“That rock was born like 15 million years ago," Foster said. "And that rock knew that my son was going to be murdered. And it knew it was going to be part of my healing process. And it knew it was going to be a voice for our people."

Foster’s voice is now a part of the Washington state task force for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and People, pushing for more police accountability so no other family has to suffer like hers.

“It's going to take the people to uphold justice, the people to say, no, we want accountability," Foster said. "And we want it now."