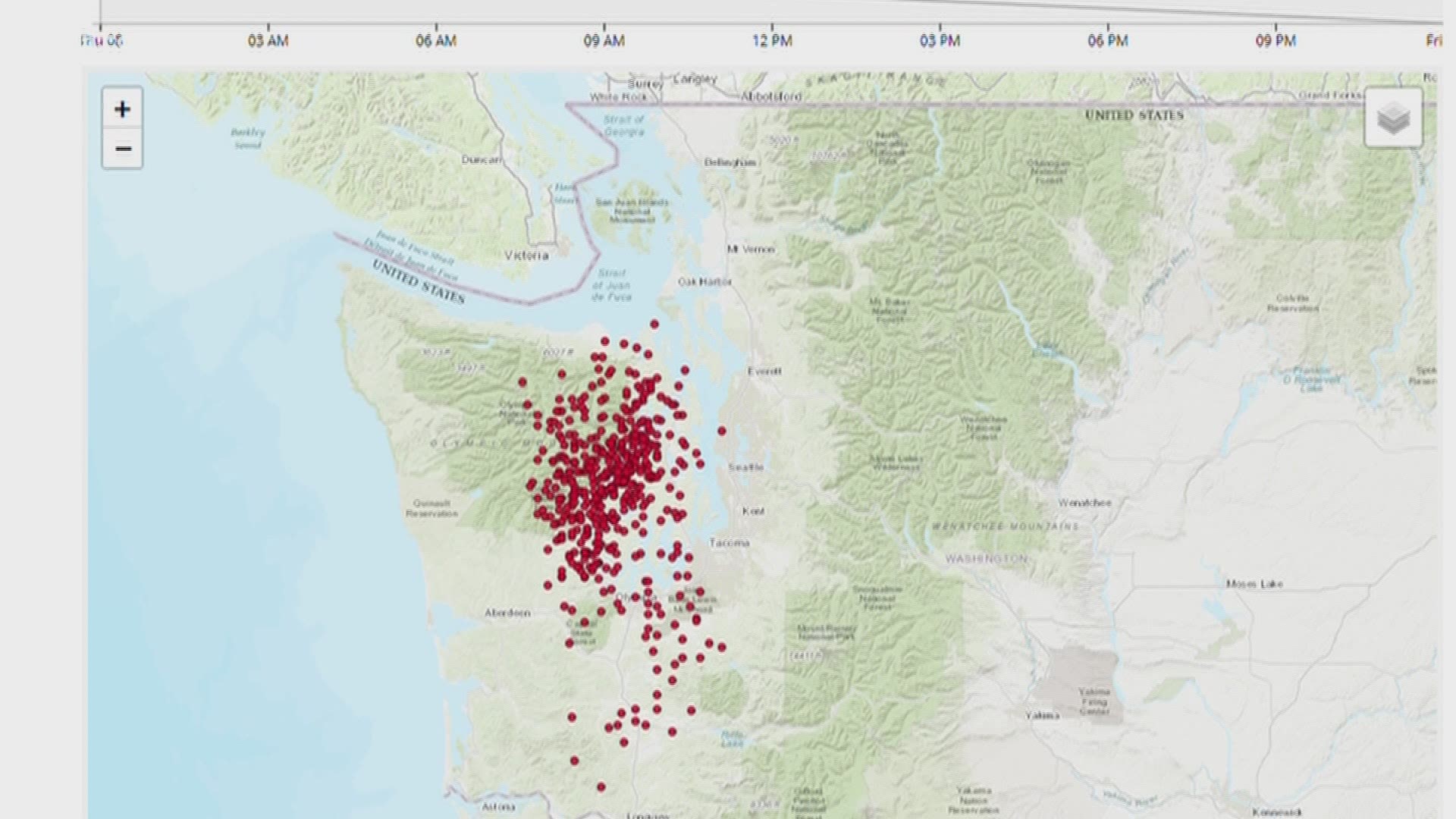

WASHINGTON — A swarm of thousands of tiny earthquakes deep under western Washington, Oregon and British Columbia started again.

You won’t feel these particular quakes because they are happening 40 to 60 miles deep, as it's believed the lower slab of the oceanic Juan de Fuca plate becomes stretched and pliable as it’s heated and melted back into the Earth’s mantle.

These have been called “silent earthquakes,” which have a deep tremor and slow slip. Collectively, they move enough to slightly change the surface of the earth near them. The tiny epicenters pop as that plate slides. They will last for weeks until the event is over.

These silent quakes release the equivalent energy of a magnitude 6 earthquake, which is in the range of the Nisqually earthquake that occurred nearly 20 years ago on the last day of February. The Nisqually earthquake was a magnitude 6.8.

Scientists didn’t even know these slowly evolving quakes existed 20 years ago.

“Maybe 2002, 2003 - that we started realizing that these tremor events take place deep under western Washington,” said University of Washington seismologist and professor emeritus, Steve Malone.

Malone continues to track these events and look at what they could potentially tell us about the giant mega earthquakes that Washington is expected to experience again.

These types of silent quakes are now found around the Earth, mostly where crustal plates forming ocean floors are pushed under continental crust. This is true around the Pacific Rim, where the quakes had been discovered a few years earlier in Japan.

The violence of these events, which can range into the magnitude 9 range, including the great Tohoku earthquake in March of 2011 in northeastern Japan, triggering a tsunami, the failure of a nuclear power plant, and the loss of more than 15,000 lives.

The scientific term for this crustal collision is called subduction. However, if the lower end of the plate moves quietly and unnoticed, the descending ocean plate is not as pliable as it gets closer to the surface. Usually, it is locked, only releasing when enough energy has built up that friction with the continental plate can’t hold it back.

How often this lock breaks in a giant quake depends on where you are. The last time it happened under Washington and much of the west coast was in January of 1700, in what’s called the Cascadia Subduction Zone. The subduction zone runs from Cape Mendocino in northern California, past Oregon, Washington, and off Vancouver Island, B.C.

“I actually do think these are giving us a window into a part of the Earth we can’t get to,” said Washington state seismologist Harold Tobin, who also leads the Pacific Northwest Seismic Network at the University of Washington. “It’s giving us stuff from all the occurrences, the little pops.”

While most earthquakes are fairly random in time, the tremor runs on a schedule, occurring about every 14 months.

But could silent quakes or deep tremors indicate that a big earthquake is coming, or at least creating a window when it’s more likely?

One theory is that it could add to the pulling force on the locked plate above it, one day triggering a massive quake. But Tobin said there has been no real correlation around the world between deep tremor followed by a massive quake in the subduction zone.

After all, it’s only been about 20 years since the quakes have even been studied, a blip on the geological time scale.

Tobin, who is an expert in subducting plates and has also spent a lot of time studying them in Japan, said they could become a predictive tool for telling us when we might expect a damaging earthquake in the same geological structure.

“I’m optimistic that is where the science is heading how," he said.