When the first earthquakes occurred on Mount St. Helens on March 16, 1980, I was working as a meteorologist for the U.S. Forest Service at the Northwest Avalanche Center. Those earthquakes also triggered widespread large avalanche on the mountain in the late winter snowpack. Fortunately, no one was hurt by the slides even though the area was popular with cross country skiers.

As the volcano became more active and generated hundreds of additional earthquakes in the following weeks, more and more scientists flooded into the region. For public safety, an area around the mountains was designated as "The Red Zone," where only people working on the eruption were allowed.

However, there was concern for the researchers traveling around the red zone in avalanche terrain. As a result, we began to issue avalanche forecasts for the mountain on a daily basis. As part of this, I and Mark Moore (we co-founded the Avalanche Center together in 1975) traveled down into the red zone to determine the snowpack stability and to check in with our volunteer weather observer at Spirit Lake (she was one of Harry Truman's neighbors).

As the eruption progressed and the bulge on the north side of the mountain grew, we decided that it was too dangerous for our observer and finally on May 8th we went down to Mount St. Helens, and removed her and all of the weather equipment. Not really understanding the potential danger, the three of us drove up to the top of the Timberline loop road to watch the sunset on the mountain -- a spot that ended up being the lip of the crater 10 days later.

As we left, our observer wanted to say goodbye to Harry Truman so we spent an hour visiting with him and all of his cats. We heard his plan in case there was an eruption. He had a speed boat and had supplies in a cave across the lake. No one really anticipated the size and speed of the event.

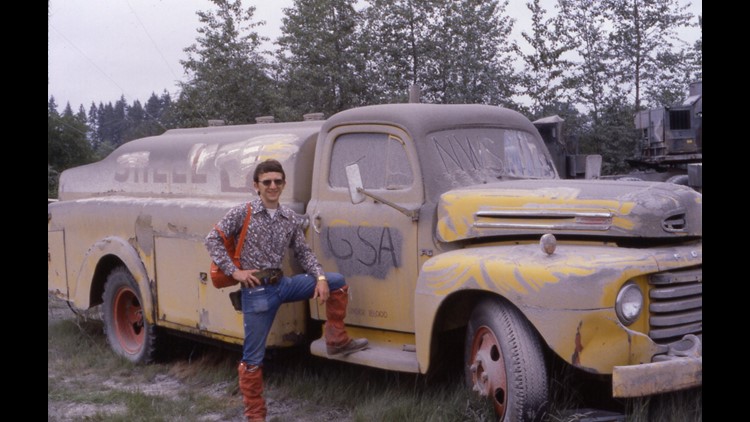

Rich Marriott's photos from Mount St. Helens eruption

Mount St. Helens erupts

The eruption happened on a Sunday morning when I wasn't forecasting, so I slept through it, but the magnitude of the eruption was an amazing realization later in the day. Weather forecast for around the mountain suddenly became important to help with the rescue efforts.

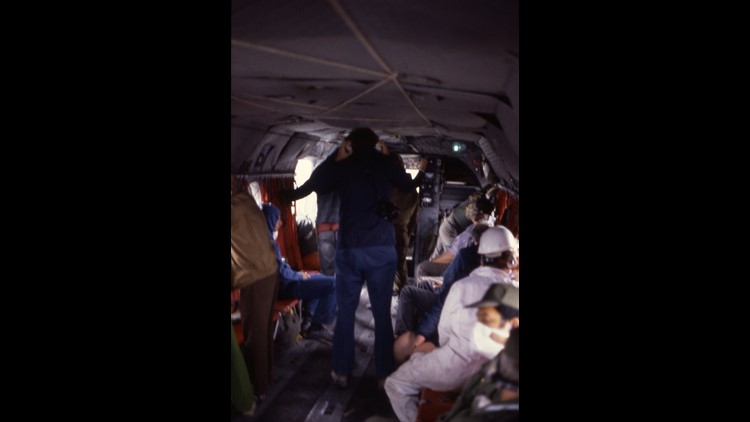

Four days after the eruption, we were invited to join a group of NWS personnel to go down to the mountain and fly on the rescue missions to add eyes to the search. The Chinook helicopters flew set grids and looked for survivors and debris.

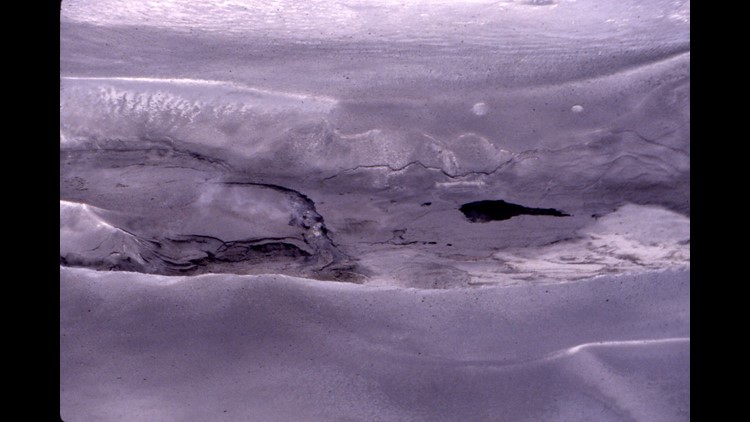

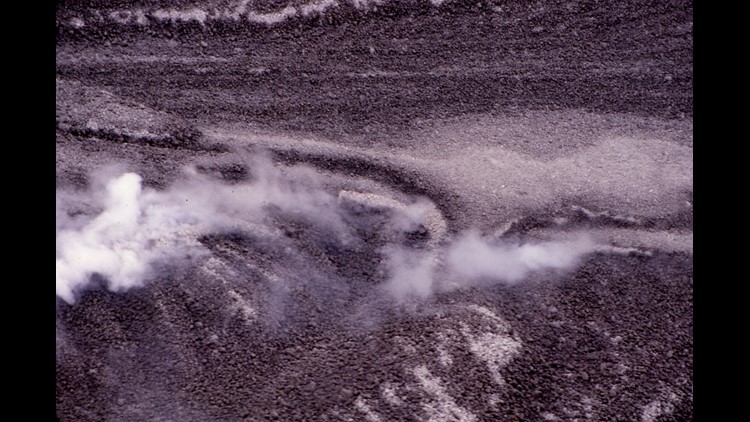

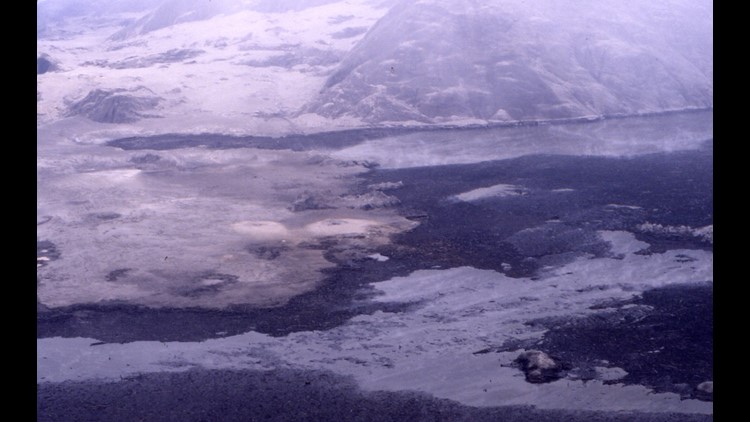

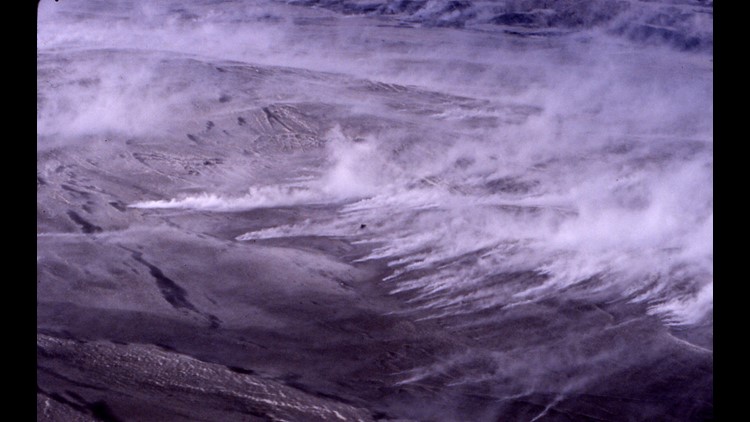

The landscape was completely transformed. Before the eruption this area was a pristine forest with a beautiful clear blue lake. It was spectacular. Now as we flew in under a low overcast, everything was in browns and grays. The trees -- where they survived -- were stripped of vegetation and laid down away from the eruption coated in gray ash. Chunks of ice the size of houses lay scattered on the mud flows, all that remained of the glaciers. Fumaroles erupted randomly spewing plumes of gases. Random craters had formed, some ringed with bright yellow which we assumed was probably sculpture. It looked like a scene from hell.

When we returned from the flights, a little shaken by what we had seen, I met Chris Wallace with NBC. He was looking for someone who knew the area to fly with them and look for interesting scenes. This was in sharp contrast to the gridded rescue flights.

I volunteered and we spent about two hours surveying all of the destruction. We saw destroyed bridges, ash covered vehicles and at least one set of human footprints in the ash. We flew low over what was left of Spirit Lake, which was filled with the remains of tens of thousands of tree and other debris. At that point the overcast, which had shrouded the mountain since the evening of the eruption, began to lift enough that we could see the rim of the crater and actually see in for the first time. For me it was then that I realized how much of the mountain had been lost.

We flew in again about a week later for another round of searching. Visibility was much better and it was easier to see the scale of the overall destruction. Mark and I had to go straight from Mount St. Helens to Crater Lake (for an avalanche training session for the Park Service). It was a unique contrast to go from the immediate destruction of an eruption to a place that had also had a massive eruption, but 6,600 years earlier, so we could see how nature heals.

And it has been fascinating over the past 35 years to see the healing taking place. It was sad to lose such a beautiful area, but it has been a gift to have seen one of the most spectacular forces on earth destroy an area and then watch it gradually renew itself.